So, who wins when it comes to bringing one’s books to market? Especially when it’s an Indie Author/Publisher doing the bringing? Well, not the author.

Perhaps that’s a bit unfair, for as in any business, the author should expect risks as well as rewards, and a lot of hard work. Every player in the supply chain from author to buyer has their own set of risks and costs. Hard work may not guarantee results, but success rarely happens without it. Once again to quote Stephen Leacock: ‘I don’t believe in luck, but I find the harder I work the more of it I have.’

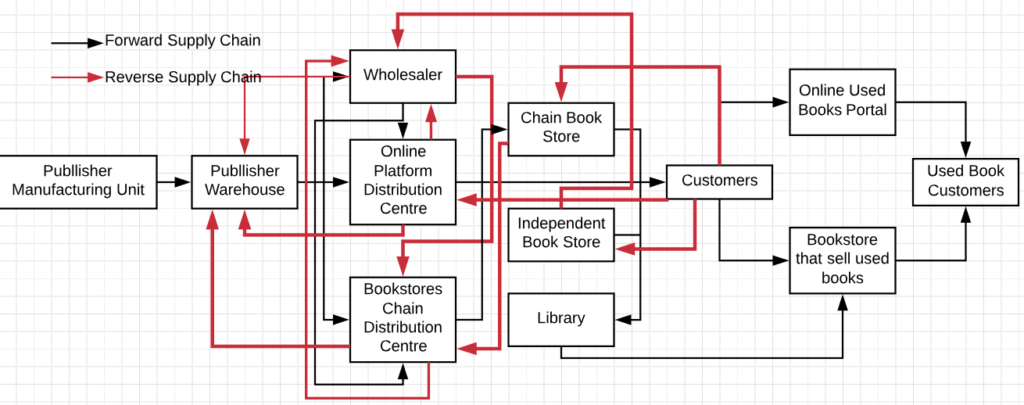

The Chart looks complicated enough, but if you are an indie author/publisher you have to pick your way through all of that yourself and more, or less. Missing from this chart are the shipping companies, perhaps the only winners in the chain.

So who wins? Even acknowledging that there are a number of needed partners in order to get my books to readers, who actually benefits?

Well, the customer. We must say off the bat the customer wins. And that is because, for whatever reason, my books were valued by my customers. Some may have bought the book out of some sort of duty to me, with no real expectation they would ever read it. The ‘win’ for them is a feeling of altruism. Pity, but thank you. For others, it may have been mere impulse, stimulated by my compelling marketing. For some, perhaps, is fame by association – owning a book written by an author you actually know! One who one day may even be famous. But for most, I hope, it was because they were truly interested in reading this book: for them I hope I met my goal: to entertain, possibly to educate. (If I didn’t believe this, why would I be in this game at all?)

(Notice ‘Library’ in the chart above: they may be a customer for the publisher but evidently they don’t have any customers themselves! I have begun persuading regional libraries to add The Treasure of Stella Bay to their collections with the hope that this ‘channel’ will at least reach some readers.)

The printer/distributor wins for sure – in my case lulu.com. Using The Treasure of Stella Bay as an example, Lulu charges me $11.13/ copy to print this book (all figures CDN$, the algorithm is adjusted for different currencies: USD, EUR, AUD and GBP). I set the selling price; the difference is my Gross Margin. Of this base fee ($11.13), x amount must go to the actual printer (Lulu contracts this out to a network of printers all around the world); Lulu keeps the remainder as their administration fee to maintain their website, server farm, their paywall, and their staff admin. In addition, when a customer orders directly from Lulu.com at the full list price ($27.70 CDN!) Lulu keeps $3.31 as their commission. That suggests I get a $13.26 Royalty per copy. $13.26 may sound exorbitant to you – and it would be a healthy margin if all my customers bought directly from Lulu – but stay tuned, there’s more to this story. And why did I choose $27.70 CDN as my retail price. Well, read on and see.

(Once I produce The Treasure of Stella Bay as an e-Pub the print cost will disappear and I will be able to charge a lower selling price; Lulu still gets their admin costs and share fees.)

The shipping company wins – in my case both the shipper Lulu uses to ship the printed books to me or my customers, but also the shipping company I use to transship my books to my own end-customers. In both cases that is mostly Canada Post.

(For e-Pubs of course there are no shipping costs.)

If my customers buy directly from Lulu they get to pay that shipping cost themselves, and that may make the total price rather inelastic to many potential buyers. $27.70 is not out of bounds as a fair retail price for a print book, but $38.65 might be. I can’t control the shipping cost – the shipping company doesn’t care how much I charge for my book – so maybe I should reduce my retail price at Lulu to $19.00 and in effect absorb the shipping cost and mitigate that sticker shock. Wouldn’t I still be making money? Hmmm, let’s see how that works out as you read on.

Shipping costs vary with quantity. The cost to me (or for you for that matter) for Lulu shipping a single copy is $10.14, including tracking, oh, plus tax of $0.81; but when I order a quantity of 10 shipping [within Canada] is $30.59, oh, plus tax, $5.98; this works out to $3.68/copy, which is a whole lot better than $10.95 for a single copy. (I doubt you as a customer are interested in buying ten copies in order to save money on shipping costs, unless you are buying gifts for all your family and friends; or maybe you are becoming a reseller.)

When I sell my book from my home office I charge $25, no tax. And I get to keep almost my full Net Margin, in this case $10.19. If I re-ship I send by Canada Post and the cost is $6.18 (no tracking) which the customer pays – once again I don’t benefit but the shipper does. If delivered by hand, no shipping charges apply, but lunch may cost 10x the cost of shipping (and I usually pick up that cost, call it ‘promotion’).

The General Distribution agents (Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Ingram) definitely win, even more so these days than even a few years ago. Here’s where things get really sticky. In addition to the assumed print costs (Lulu’s admin fees are in there somewhere still) these distributors keep a $13.85 Distribution Fee, thus reducing my Gross Margin to $2.72, but Lulu still keeps a Commission share of $0.54 leaving me with a Net Margin of $2.18. Hmmm. (And now you know why my original retail price at Lulu is $27.70.)

The Bookstores win, maybe. And if they win, I win, maybe. Independent booksellers, or other independent retailers, may choose to stock one’s books on a consignment or contingent basis. ‘Contingency’ means uncertain and consignment means the producer carries the cost of the inventory, not the retailer. The retailer charges a commission, if she sells any books, out of which she covers her operating costs. This commission ranges from 20% of the sales price up to 45%. Both of these factors are negotiable though some retailers are pretty stiff. Most of my retail partners have a policy (or have agreed, bless them) to a commission of 30%. These retailers are most comfortable with a retail price of $22.50 – worried about price inelasticity above that. (And let’s not talk about HST shall we?) At $22.50 and 30% my Gross Margin is $15.75, but my costs (Lulu and shipping) average out to $13.33/ which leaves a Net Margin of $2.42. At 35% I make even less and need the retailer to charge a higher price; at 40% the algorithm goes out of range and 45% is impossible. Hmmm. Same result as for General Distribution but a lot more work and risk. And unless the retailer prominently displays my book the impulse buying traffic is much reduced. The residual risk is that when the retailer tires of holding unsold inventory he sends the books back to me (shipping company wins again) or sends them to the dump.

So, the bookstore strategy may not be as effective as we thought, but at least it does offer the potential of exposing my book to customers who otherwise would never know of it. And that is the name of the game – exposure.

What about big box bookstores?, you might ask – just forget about it. In Canada there is only one – Indigo/Chapters (and its subsidiary smaller retailer, Coles). Oh I suppose I should include Walmart and Costco who sell large volumes of volumes, but like Indigo, they’re not interested in helping indie authors.

Me – I’ll let you draw your own conclusions as to whether I win. As in most retail businesses of commodities or regular items, books have a very small net margin, even if you are managing costs closely. So the only way to make a decent income from selling books is to sell a lot of them. If I could sell thousands of copies out of the back of my van (assuming I even had a van) at a net margin of $9.58 I might be able to make a financial go of it. Okay do the math: 10,000 copies at 9.58 makes slightly less than a 6-figure salary. Or alternatively, I need customers to buy 7224 copies direct from Lulu. Per annum. Hmmm. That’s quite a lot of books.

Even still, I need to sell 666 books with an overall net margin of ~$3.00 before I am able to recover my development and marketing costs (mostly the cover designer’s fees, but also including lunches!) of ~$2000. And selling 666 copies is a devilishly difficult task. (I don’t actually factor in my own time in drafting and editing and polishing the manuscript; in the case of The Treasure of Stella Bay, maybe 1250 hours; and then we should add in the hours spent marketing and promoting it, ordering and shipping it. Oh and what about the hours dreaming up a marketing plan, and the hours of fretting and procrastinating?! What should my hourly rate be? It should be my opportunity costs – the cost of not delivering consulting services. To cover all those ‘costs’ I would need to sell another 40,000 copies of my book! Out of the back of my van??!!?

Hence the need for the other sales/distribution channels – they are the only way I am going to get a chance at any serious volume of sales. Through General Distribution and retail booksellers, my books have the potential to reach many more buyers than I can reach on my own, but then, at $2.18/copy, I would need to sell maybe 100,000 copies to cover my [hypothetical] opportunity costs. And even so, somebody, mainly me, still has to drive those thousands of end-customers to those sales channels. Yikes.

So, do I win? Of course I win. I may not make any money writing but I do have episodes of flow and derive moments of happiness. It’s called psychic income which doesn’t pay the rent but is nevertheless satisfying.

And I win if my readers have enjoyed my work.

I have long said my goal in writing is not to get rich, necessarily, but to be read. But how many people are needed to feel ‘read’? A few dozen? A few hundred? A few thousand? Even if I sell 10,000 copies I won’t be rich, but I will be happy.

Doug Jordan, reporting to you from Kanata Ontario

© Douglas Jordan & AFS Publishing

All rights reserved. No part of these blogs and newsletters may be reproduced without the express permission of the author and/or the publisher, except upon payment of a small royalty, 5¢.