I was standing in the checkout line at the local Waltermart grocery store in Trece Martires, Philippines, this week when it struck me, and not for the first time, ‘Where are all the foreigners?’

There weren’t any. Well except for me of course.

Waltermart is a typically modern supermarket, not your stereotypical wet market we Westerners expect in third world countries. I gazed over the people lined up at the other eight or nine checkout cashiers, and up and down the aisles as shoppers pushed their grocery carts, carefully selecting groceries and household needs for the week. And everywhere I looked, all I could see were Filipino faces (well, actually, mostly Filipina faces). There were no Arab faces (or Syrian, or Lebanese or whatever else looked Middle Eastern), there were no black faces (American, Jamaican, Nigerian or middle, western, southern or North African), no South Asian (Indian, Pakistani, Punjabi, or whatever other of 250 ethnic groups), nor East Asian – Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, nor Chinese. Not even Chinese, even though there are a few million Chinese who have lived in Piliñas for many generations. Only Filipinos.

Only Filipinos. And somehow that was surprising.

It used to be like that in Canada. Well, not that wherever you looked you saw only Filipinos. Rather, wherever you looked you only saw white people. Certainly in small town Canada. Even up to about 40 years ago, except perhaps in the three major metropolitan areas, you rarely saw visible minority people, only white people, like me. As a kid growing up in the 1960s in Canada, that was my normal. That was most Canadians normal. I suppose people in the prairie provinces experienced ‘Indian’ people more than we Southern Ontarians did but these ‘Indians’ were aboriginal natives, not immigrants from South Asia. That was our Canada.

And I miss it.

Being an old codger, and a privileged white guy to boot, you could call me racist, a white settler, a colonialist occupying aboriginal land, or any number of pejorative names these days, seeing my defence of my ‘Canadian’ identity, as a sign of intolerance, which I deny.

But that is not the point.

The gradual merger of the world’s cultures, and even races, because of advances in technology and transportation, not to mention migration, is inevitable, and in an idealized sense, desirable. We are gradually, perhaps even rapidly, rearranging our species into a single common culture in a global village. But in the process something is lost.

Canada proudly claims to be a land of immigrants, and there is no doubt that without a hundred and fifty years of settlers, this land would still be a vast wilderness, not the settled industrial modern and prosperous country it has become. But most of those settlers were migrant Europeans – not just British or French – and these white Caucasians had largely integrated into English (or in Quebec, English or French) Canadian society, generally within a single generation.

But now, we white colonialists are rapidly, willingly, giving away our identity to millions of new immigrants coming mostly from third world countries. Visible minority people.

Visibly different people can never overcome their skin colour, of course, and so long as they are a minority in a predominantly white society they will always be seen as at least a little bit ‘foreign’ no matter how culturally integrated into Canadian English society they have become. One of my son’s friends is ‘Japanese’, and even though he is third generation Canadian, and ‘English’ Canadian in language, interests and behaviours, he cannot escape being Japanese.

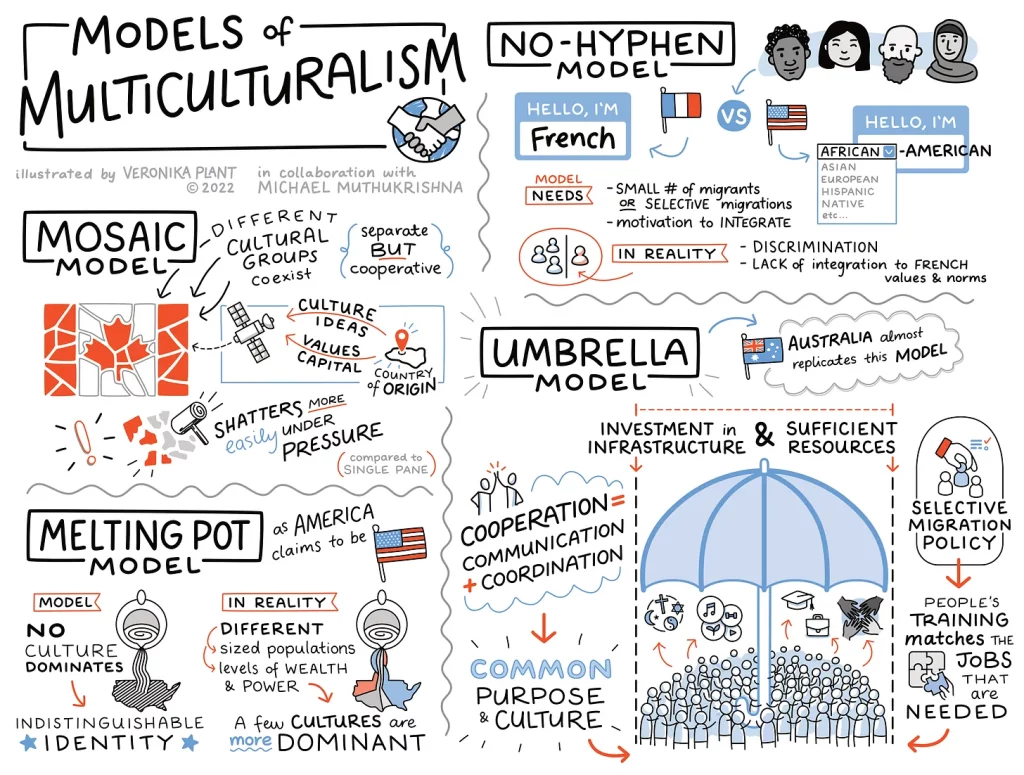

Multi-Culturalism is a strategy, whether explicit or organic, to accommodate the co-existence of different ethnic groups in one society. But in the process, multiculturalism segregates these groups, even into isolated ghettos; and at the same time this process brings about the gradual dilution of the original common culture.

Not only has Canada now been occupied by millions of visibly different immigrants, under our ‘multi-culturalism’ policy (cynically introduced into Canada in the 1970s by Trudeau père to subvert Quebecois separatism) these new Canadians are encouraged to celebrate and preserve their previous cultures, (nothing inherently wrong with that), visibly, proudly. Moreover, many of today’s white Canadians (most often ‘progressive’ and ‘woke’) now so promote other people’s cultures (and suppress the celebration of traditional British and French cultures out of some sort of guilt), that a particular Canadian cultural identity is no longer easily apprehended.

Paradoxically, while English white Canadians passively undermine their own culture in Canada, they eagerly travel to other countries to seek out traditional cultures there: they want to see kilts and bagpipes in Scotland, and Big Ben and pubs in England, berets in Paris and lederhosen and Oktoberfest in Germany. And then they are surprised when they get there that the suburbs and inner cities are overwhelmed with hordes of decidedly not German or French people.

But as much as Canada as a political strategy encouraged differences in the cultural make-up of Canada, it’s not clear to me that this outcome is even desired by the Immigrants who migrated here from their native lands.

I had a French language instructor some years ago, a PhD in philosophy, from Haiti. His job as an FSL instructor was to encourage the class of (comparatively advanced) adult students to engage in conversations on current affairs topics. The topic that day was multiculturalism, probably too complex a topic to be managed readily by even intermediate level French speakers. The instructor was provocative and challenged those in the class who argued for multi-culturalism. Quite passionately he replied, ‘I am a black Haitian; I can never escape being a black Haitian; even my French, and my English, is spoken with a Haitian accent. But I didn’t immigrate to Canada to be Haitian; I came to be Canadian. I can celebrate my Haitianness in my basement. I don’t want to celebrate it in the streets.’ That was 15 years ago.

One of the corollaries of the multiculturalism policy, and the ‘open doors’ immigration policy increasing numbers of visible minorities, is to increase visible minority representation in institutions and the ordinary fabric of society. The argument was, not altogether wrong, was to have people in public and everyday roles who looked like other visible minorities. Today I walk the malls of Ottawa, or Markham, or Mississauga and hardly see anybody who looks like me,

Trudeau fils declared, some fifty years after his father set it in motion, Canada is the first ‘post-national’ state, with no discernible Canadian cultural identity. It would appear that Trudeau père was successful in his strategy of subverting Canadian identity, of either English or French Canada.

But was he? Quebec nationalists have conducted two referenda seeking to achieve legitimacy for the separation of Quebec from Canada. Why? To seek to preserve their French language and their cherished French-Canadian cultural identity of 400 years in Canada. I suspect many English-Canadians secretly admire their courage and wish it for themselves.

Third-world countries such as The Philippines have no such existential issue. (They have other existential issues but national identity isn’t one of them.) This is in part due to the natural fact that third world countries are not the target of immigration from other third world countries, and certainly not from first world countries (except perhaps for retirees trying to salvage something from their meagre pensions and seeking companionship). Moreover, they celebrate their own culture and cultural heritage; they pay close attention to the symbols of nationhood – holidays, the flag, the national anthem.

The Global Village

It seems to me, the idealist in me, that the concept of ‘global village’ relies on the notion that human beings are one species and should come together as a single uniform community. Multiculturalism and diversity are antithetical to this notion of global village. A global village is not a hodgepodge of separate societies tolerating one another and celebrating their differences, they are as one culture, a vast melting pot. But this ideal seems to me still a far-off dream.

Human beings for all but the last century of their existence, have lived locally. Most still do. They didn’t venture far from their village; people outside the village spoke a different language, or at least dialect, within mere miles of each other; only adventurers, traders, merchants and entertainers commuted. People from other villages were always viewed with suspicion, if not actual fear. There have long been marauding tribes but these, and their victims, hardly regarded each other as members of the same global village. One might think of the Roman Empire as the closest thing humans have come to as a global village, and lasting for 500 years was some sort of miracle. But even the Roman Empire succumbed to barbarians who did not appreciate the value of such a vast collective; for that matter, the Roman Empire was hardly global.

Human beings are tribal. They are hard-wired to value sameness, not otherness. Tribes fashion cultural habits and artifacts to emphasize their belonging (and in consequence differentiate themselves from the others). These differences took generations upon generations to build; they are not easily extinguished or assimilated. Nor should be.

My tribal village is English Canada, or even more parochially, South Eastern Ontario. First substantially populated by United Empire Loyalists, refugees from the revolutionary American states, and then by waves of economic migrants from the British Isles, they cleaved to the Union Jack, the stability of the monarchy, and the English notions of representative democracy, and of good government and the rule of law, and all the historical tabs that signal those concepts. Other tribes cling to their own symbols of cultural heritage of hundreds of years, and fear and resent the rush to extinguish them for unknown and uncertain values seemingly being thrust upon them. They, as much as me, feel the loss of a part of our respective identities as the cultural characteristics that formed them are gradually, or worse, rapidly, rent from us.

Multiculturalism may be a transition process from traditional segregated cultures to a unified common culture – a global village. But as in all change, something is lost as well as something is gained.

The global village is more than multi-culturalism. It is homogeneity, an ideal that may be inevitable. But our transition to it needs to be gradual. After all, evolutionary change is a slow process. We need to give it time.

Doug Jordan, reporting to you from Trece Martires, Philippines

© Douglas Jordan & AFS Publishing

All rights reserved. No part of these blogs and newsletters may be reproduced without the express permission of the author and/or the publisher, except upon payment of a small royalty, 5¢.