To be an author takes a load of courage, or maybe it’s unadmitted hubris. Authors – well maybe not all authors – believe in themselves; they have to. They have a story to tell, and a belief they have the skills to tell it, well.

Well, not always. Deep down, or maybe close to the surface, they have doubt, lots of doubt. They worry that they don’t have the talent, and they fear that some reviewer will confirm that fear; others hope for affirmation, if not approbation.

So, to have some reassurance that his or her manuscript is ready to face the outside world, the next step in the author’s journey to being published is having a capable person edit his/or her work. Or should be.

Editors, on the other hand, seem not to have the same misgivings.

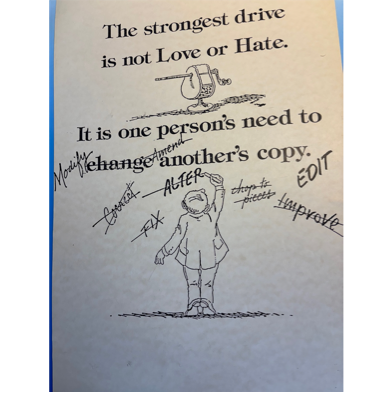

(This cartoon was given to me as a poster, and signed by all my staff, when I was VP HR at Mitel Corporation, 40 years ago. I’m sure it was affectionate feedback.)

So, to give his manuscript to an editor is a ritual authors are likely reluctant to engage in. All that (‘positive’) feedback, and opinion disguised as ‘suggestions’, may not be taken well, even if the author smiles savagely in thanks to the editor.

Knowing this, the editor has a very challenging job: giving feedback and providing advice, guidance and suggestions, all without usurping the author’s ownership of his own opus – and undermining the relationship – takes a tremendous amount of tact, diplomacy, and finesse. And likely, courage.

Beyond diplomacy, and due regard for the author’s tender ego, what are some requisite attributes for an effective editor?

- Well, rather obviously, a good command of the language (let’s assume here the document is in English): spelling (despite the help of spellcheck software) – especially the misplaced homophones not caught by spellcheck, and grammar (in spite of ‘Grammarly’ software – Grammarly is not the last word on grammar, nor is Fowler). The problem with ‘correct’ grammar: not everyone agrees as to what is correct. (I’ve written more on this here, and here.) The author, having his own peculiar style guide, may have deliberately chosen to split that infinitive, to use the passive voice, punctuates with a variety of separators – not just commas but also dashes, semicolons, and the occasional oxford comma; it’s not for the editor to insert his sense of ‘proper grammar’ in place of the author’s. Except, if the meaning is not clear: if idiosyncratic grammar and punctuation confuses the reader, the editor is obliged to point this out to the author. This also includes the patience and eloquence to try to explain the problem to the stubborn writer.

- The editor needs to be tuned into the logic of the text. The secret to clear writing is clear thinking. But the writer, fully immersed in his story in his head, may not realise his text has left out some important bits, or they are in the wrong place.

- Closely related to logic is structure. There are different ways the writer can construct the plot and roll out the story but the pieces of the puzzle need to come in a rational way, not out of sequence to the logic of the structure. Timelines may go back and forth but you can’t have an event later in the text that has no logical connection to events earlier in the text.

- Closely related to the logic problem is ‘the twist’: the introduction of a new character or event out of the ether, or out of convenience, to bring the plot to a satisfactory conclusion. This is a particular problem for mystery genre writers.

- Closely related to structure is ‘point of view’ – ‘POV’ in the biz. The author has to decide whose story is this anyway, and then stick to it. The author needs to determine who the narrator is, the ‘person’ delivering the story to the reader: the professor writing a learned text, the biographer telling of the life of the subject, the memoirist telling his own story. The memoir is told in the first person, naturally; a work of fiction can be told in the first person as if by the main character himself; more commonly is the fiction told from the point of view of the main character, but instead of in the first person is told by the involved narrator in the third person. The problems with pov for the author is sticking with it: the author can’t shift from one pov to another in the same text. The skilled writer understands this problem, selects his POV at the outset and sticks with it. But in the flow of things, sometimes he will slip up. More insidious is when the plot requires new information that can only come from a source different from the main character as narrator. This is the problem of omniscience: if the narrative is told from the first or third person personal point of view the narrator can’t know what is in the mind of another character in the story. There are devices to overcome that problem but often these are unsatisfying to the reader. To overcome the individual pov problems the author has to adopt an omniscient narrator point of view from the outset. POV can be difficult to sustain by the author deep into his draft, but to fresh eyes, i.e., the editor, the pov problems are usually more apparent, if not jarring. Now the problem is, how does the editor explain to the author that one of them has lost the plot.

- Okay, one more structural problem the editor has to be vigilant for is tense. I mean, the relationship between the author and editor is tense enough but here I’m speaking of verb tense: past tense or present tense. Most authors prefer past tense as the most natural voice for a story that evidently has already occurred. But many authors prefer to use the present tense, as if the story is actually happening as the reader reads it. This tense is more conducive to creating energy and, dare we say it, ‘tension’ in the reader, more immediacy, as if the reader is a direct witness to the events of the story. The problem with tense is something like the problem with pov. Once you decide which tense you’re going to use you have to stick with it. And when events in the present require knowledge of something that happened in the past, you either have to go back to the place in the narrative where it should have occurred to insert the events, or otherwise get tangled up in complicated past imperfect or subjunctive tenses. The problem for the editor is to point out these lapses and then comfort the writer who realises what a lot of work he now has to do to fix these problems.

- Genre bias. We all have our biases and that’s no less true for editors. It is likely that editors – masters of grammar and style – will have preference for some genres over others. Editing technical papers requires not just good command of language but domain knowledge as well. An editor of historical fiction will likely struggle with speculative fiction; fantasy/romance writings will not go over well with biographers. Editors should probably decline to review a manuscript in a genre they are unfamiliar with, or don’t appreciate. I don’t know who poets can go to for feedback.

- Unnecessary content. Authors love their words, and their sentences, but for the editor to persuade the creator there are ‘too many words’ is a difficult conversation. The saving grace is that the writer, even though in love with her own words, soon forgets them once they have been deleted, especially if the new sentence or paragraph reads much more smoothly. One of the great advantages of word-processing software is the ease of cutting & pasting text: cutting from the manuscript and pasting in a reserve file for use some other day in some other manuscript, assuages the authors angst over the loss of her children.

- Close cousin of too many words is too few. The author expresses a scene or an action ‘economically’ leaving the reader to ponder and guess what the writer is getting at. This is an opportunity for the editor to invite the writer to embellish and add more colour and flavour to the passage. It’s also an opportunity for the editor to help the writer with his block by offering some of the missing text himself, at risk of hijacking the opus.

- Cliché vigilance. Close corollary to the author’s love of his own words is the lack of awareness of the use of clichés in his or her text. Much of the content of our minds is subconscious absorption of thoughts, ideas and expressions that come from our social existence, the memes of our lives. Fully immersed in the creative process of bringing an idea into a written story the creator doesn’t realise the idea has already been explored by others, overused even; the highly descriptive imagery, simile, metaphor, the comfortable turn of phrase, is a horse already beaten to death. The editor needs to suggest, delicately, the author’s unoriginality.

- Fact checking. The editor is not the researcher – that’s the author’s job, even if the author delegated the task to an intern – but the editor has to pay attention to the doubts and questions that arise from the mists in his mind that that statement, claim or name the author used isn’t correct. When the editor is not a domain expert, and assumes the writer is, or at least has done the investigation of the facts, it’s natural to trust the author to have done his job. The problem comes when the author’s faulty knowledge goes unchecked into the text. The editor has to flag anything that ‘just doesn’t appear right’.

- ‘Show, don’t tell.’ The classic stylist advice for every author. Of course it is insulting to the intelligent reader to explain the obvious. Even children will roll their eyes at ‘obvious-man’. But for writers of fiction, memoirs, biographies – any narrative effort whatever – telling is what the job is. Showing without telling is hard, nye, unrealistic. I have struggled with this ‘challenge to writers’ many times, usually solving the problem by giving the job to the characters in my novels through dialogue: it’s easier to have the characters telling each other what’s going on than describing the scene itself. So, the advice for the editor fresh out of creative literature class, unless it’s painfully obvious, shut up about it. I read recently in a delightful novel about a book-store owner, the origin of this hoary guide to authors: it was intended for screen-play writers, not novelists. The playwright tells the story largely through dialogue, naturally, leaving the director of the play to create the scenes and stage the play to show the audience what is going on: ‘Show, don’t tell, is a complete crock of shit. It comes from Syd Field’s screenplay books but it doesn’t have a thing to do with novel writing. Novels are all tell, they aren’t meant to be imitation screenplays.’

- Finally, there is accountability and reputation to accept and protect. Authors often want to acknowledge the contribution of the editor, without which this book might never have come to being published; (this is even more of a problem if the book is self-published). But if the book is sloppily written and so published, some of this mess falls to the editor. (I wonder if many editors publish under a pseudonym.)

In my experience as an editor – of which I’ve had decades of practice and acquired a ton of self-learned expertise (ref. above cartoon) – editing is exhausting work. You have to read every line, and then, when you stumble over something, go back and read it again, then make some markings in the document, or the margins (digitally or in hard copy (the old fashioned way, with red pen)), and then review it all with the writer. Remote computer access has rendered this process somewhat semi-antiseptic: e-mail the marked-up document to the author and let them go over it on their own, stewing and seething in gratitude and confusion at all this wonderful feedback.

I guess the advice to editors (if that’s what you want to do), is, show, don’t tell. But with tact and diplomacy.

Doug Jordan, reporting to you from Kanata

© Douglas Jordan & AFS Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of these blogs and newsletters may be reproduced without the express permission of the author and/or the publisher, except upon payment of a small royalty, 5¢.