Alex’ Choice? Shouldn’t that be Alex’s Choice?

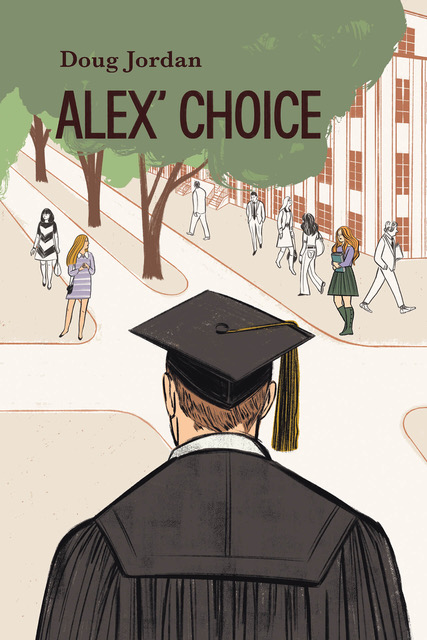

Amazing the number of ‘inquiries’ (and some of them quite sharp) I got as to my use of the apostrophe in the title of my latest book, Alex’ Choice. Even before the book was published and I was testing the cover design with my blog followers I got more feedback on the spelling of possessive case for Alex than I did for the cover design. The cover design gradually was revised to the cover you see now but my use of the apostrophe persisted. ‘My title, my choice’, I said to myself, petulantly.

As this discussion was occurring with my readers, a sudden blow-up on whether to ‘s or not to s suddenly emerged as to correct usage of Harris (as in Kamala), and even in Walz (as in Harris’ running mate Tim). There appears to be 3 kinds of readers out there (or maybe four or five): those who cleave to the apostrophe s in all cases, those who prefer the dropped s in some cases (especially those words ending in s), and those who don’t notice, (or perhaps do but are polite enough to hold their opinion to themselves). (And did you notice the Oxford comma in that last sentence?)

Maybe I’m too sensitive, but I took the feedback personally: ‘You call yourself a writer and you can’t even get your apostrophes straight?’

I concede to being sensitive, but I also have a strong (or shall we say stubborn?, self-absorbed?) sense of my own command of the English language. I’m a pedant just like many of my critics. I too cringe at misplaced commas, dangling participles, errant antecedents. I have a compelling need to get out my pen or marker and ‘correct’ errors in the text of books I am reading.

But I’m not a slave to rules of grammar if it doesn’t suit me. I’m also a rebel. If the rule doesn’t quite fit with my sense of coherent smooth reading, I change the rules. I am arrogant enough to adopt usage to suit myself, or at least my purpose. (I’ve written on my writing style in a previous blog post: check here.)

So, pedant that I am, I took the criticisms to heart and consulted many books on English usage seeking not to conform but to defend myself.

The bible on ‘Modern’ English Usage, by Henry W. Fowler, (the first edition of which was published in 1926 and revised a number of times since), equivocates on ‘s usage.

Strunk and White, the American English alternative to Oxford Fowler, insists that s’s is correct.

The New York Times and the Washington Post style guides insist on ‘s following any word indicating the possessive case, including words ending in s, z, or x. The AP style guide prefers no s in these cases.

My personal favourite book on punctuation proper is Lynne Truss’ Eats, Shoots & Leaves and she leaves the question dangling: the answer seems to be, both versions are acceptable, so long as the writer is consistent.

And it turns out, the usage of ‘s following a word ending in s (or words ending in z, or x which sound like s) is optional, or at least varies with the person who wrote the book on rules of grammar. And there have been dozens and dozens of books on [English] grammar written over the last 300+ years.

The rules of grammar are present in every modern written language (and probably the unwritten ones too, except the rules aren’t written down); they have emerged over the last thousand years, or thousands of years if we go back to the ancient languages, and especially Latin, the icon of precision in writing. Grammar is necessary to keep the text as clear and logical and as unambiguous as possible. Without a rule book, people try to communicate in all sorts of chaotic and random ways. And the rule makers, and the rule enforcers, have to be forever vigilant lest the mobs destroy a perfectly good working tool. This is true of the spoken text as the written text, though we seem to be more forgiving of oral than written communication. In polite company it is a social risk to correct someone’s grammar, even with a knowing glance to another person in the audience, but if you point out the interlocutor’s error you risk two things: alienating the other, and opening a line of defense – ‘I didn’t say that?’ But in written text the evidence of the error lies there naked, with no possibility of escape from examination.

Grammar is there as an aid to speakers, and writers, to gain accuracy of communication. It’s a necessary thing. But it turns out these ‘Rules’ have evolved over time from everyday usage, and from style, and it must be said, at times arbitrarily, if not autocratically or dictatorially.

But there are always rebels amongst as well as police. I for one consider myself a literate person and believe I know my correct usage, even if I don’t remember the name of the thing – what is a subordinate subjunctive clause? I find myself cringing at a phrase, or spelling, or misplaced modifier that just isn’t right or rings poorly in my ear. (I wonder if speed readers miss these grammatical faux pas, or do they trip up over the writer’s error, only faster? I don’t know about you but I gave up speed-reading long ago even after I took an Evelyn Wood speed-reading course in university. I always wondered if I was missing something. So when I read, it tends to be aural in my head. (I swear, I don’t move my lips.) So if the sentence or the phrase doesn’t ‘sound right’ to me, it trips me up. I may have to read the sentence two or three times, perhaps take out my red pen and correct it.

(I rationalize my slow reading habit (nominally at the speed of the spoken word) as homage to the author (especially so now that I’m an author myself): the writer spent umpteen hours and joules of energy trying to get that sentence or passage right, I figure I owe it to him to read it as he intended. (Which only raises another issue, if I read the passage slowly enough to get what the writer intended to write it risks exposing bad writing. Oh well.))

This blog post is not intended to be a justification of the gate keepers. They have their limits; and so, some conventions are rubbish, and like Churchill, up with which I will not put. As I have said in a previous post on my writing style, I freely use constructions that conventional rules frown upon: I often start a sentence, even a paragraph, with And, or But – usually to highlight an argument with the previous sentence or passage; I like semi-colons to join linked thoughts in a single sentence; I use colons often when a list of thoughts follow, and I use Oxford commas in front of an ‘and’ in series; and I have my conventions with quotation marks.

Human beings were oral long before they became verbal. (Puzzle that one for a minute: by oral we mean spoken, aloud; by verbal we mean written.) The written language attempts to convey meaning the way the spoken word intended. Of course, many people speak incoherently but since conversation happens in real time the interlocutors have a chance to question and clarify what was said. But in written language, the writer is not there to explain what he meant and the reader has to hope (or guess) what she read was what the writer intended. This is especially true for punctuation, and the apostrophe in particular.

Punctuation is a subset of grammar, and a necessary subset as well. And like grammar there are rules, and many of them sensible, necessary rules. Used properly they keep the reader from being confused about what the writer may have intended.

Apostrophes are a most contested element in accepted punctuation. It is the one punction that seeks to mimic speech. Speakers are lazy, and efficient, they skip words and collapse and combine words because it is faster and more efficient, to the speaker and the listener, to leave out words, or parts of words (or in some cases, numbers). We don’t say can not, we say cant (but spell it can’t; instead of 1999 we shorten it to 99 (’99); we don’t say ‘that wallet belongs to him’ we say, ‘that’s his’; we don’t say, the house of Mary, we say Mary’s house; and we don’t say, it is the rabbit’s fur, we say it’s its fur!, (despite the constant consternation of confused writers).

The apostrophe signals to the reader that expected letters have been left out (but not forgotten): I‘m for I am; he’s for he is; you’re, for you are (which can seriously confuse the listener, if not the reader, between you’re and your, and for that matter, they’re, there and their).

So far so good, but what’s not quite so clear is why ‘s has emerged as the possessive. Why s? why not ‘n or even zed. One theory is that the third person possessive adjective (and pronoun) evolved as his; that’s ‘hims’, didn’t sound right so it got shortened to his. Hers evidently followed: ‘That cup belongs to her’; shortened, the s replaces the ‘belongs to’ and becomes, that’s hers, (the familiar s is added to her, mimicking the possessive hims (and maybe because, back then, way back, there was no word for her, or hers, because females didn’t own anything – everything was his). (This still doesn’t explain why s rather than some other letter to indicate ‘belongs to’ by a letter at the end.

I suppose when people began to take on names, Gronk didn’t need to say, ‘that stick hims’, he said, ‘that Jons stick’ and later it became ‘that’s Jon’s stick’ with that Johnny-come-lately apostrophe stuck in the middle.

So far so good, but what are we do about Gus? The stick of Gus became Gus’s stick. But to many people, all those s-es sounding together became clumsy to the tongue, and to the ear. It even looks clumsy on the page. So common usage in the 19th century was to drop the superfluous s and just leave the apostrophe to indicate the missing words (and letters). Hence Gus’ stick. But even that singular s sounds clumsy so in the 20th century, Fowler, and Strunk and White began adding back the s: Gus’s stick. And I’m pretty sure many of my arm-chair grammarians, schooled in the second half of the 20th century, agreed: Gus’s; they have a hard rule about s’s.

So, I generally favour s’ in singular words ending in s, without the superfluous s; but the title of a book is a pretty exposed place to leave doubt in the browser’s mind, especially the critic’s mind. But to me, Alex’s has just too many s sounds altogether, and Alex, followed by Choice was one to many sibilants together. So I dropped the s after the apostrophe and let the devil take the hindmost. In the reader’s ear he may actually hear Alex’s but they still see a quieter Alex’. So I decided Alex’ Choice is how I would present it, and I know I’m not wrong.

But here was one more potential consequence, having to do with marketing. Would the apostrophe no s offend the grammarian browsers? causing them to pass over the book? Or would the grammatical ‘error’ cause them to stop and study the book more closely? I decided on the latter potential outcome and stayed with Alex’ Choice.

Like I said, self-serving, stubborn.

Doug Jordan, reporting to you from Kanata

© Douglas Jordan & AFS Publishing

All rights reserved. No part of these blogs and newsletters may be reproduced without the express permission of the author and/or the publisher, except upon payment of a small royalty, 5¢.