If you are a visual reader, you had no difficulty with the word flow in my title and begin to wonder what this article was going to be about. But if you are an auditory reader you may have seen the word flow but your brain might have ‘heard’ the word Flo, and you might begin to wonder who this woman Flo is, and why is Doug writing for her.

Reading is not an innate skill. We learn to read. Language is not innate either. It is learned. We arrive in the world and our infantile brains are flooded with sensory input, but we have no words for what we perceive, nor concepts either. (The brain must have some sort of protective mechanisms to avoid sensory overload – imagine, ‘burnout’ in the first 36 hours. Maybe that’s why babies sleep so much. Maybe that’s why anxiety afflicted adults sleep so much.) We learned early to sort things out, prioritize, categorize and ignore. We couldn’t speak but we could cry, and we learned very early that when we did, that god-mother came.

For much of human history, philosophers, and even more modern day evolutionary biologists, assumed that homo sapiens, born with large brains and elastic larynx, was uniquely capable of speaking, but nevertheless was not fully conscious until it had invented speech[1]. Psychologist Steven Pinker, and others, have since reversed that thinking and have postulated that the human brain had developed the capacity to formulate complex thoughts and then found the words to articulate what they were thinking and communicate with others. No doubt this began with mothers grunting in a particular way instructing their young progeny to use a fork not their fingers! Turns out mothers have influenced our development in more ways then mere manners; it is after all why our first language is called our mother tongue.

Our senses, hearing and seeing, and the rest, function automatically, but what we see and what we hear has to be converted by the brain into something it comprehends, a concept, some sort of neuro-electric synaptic connection. It then compares the specific thing it is perceiving into a generic thing already in memory, somewhere. The eye records a photon image and the retina converts it to a neuro-electric signal that is transmitted to a particular place in the brain where it resonates with previously perceived concepts (or parked in a new place in memory if never perceived before). ‘Oh look, a ‘dog’ (whatever that is in a synaptic pattern). It’s not the same dog as I[2]saw yesterday but it is a dog’. The image of the dog is perceived and the concept of ‘dog’ appears in the brain.

The ear captures the sound of barking and the brain parks that concept somewhere in the brain too; and the brain soon learns to associate ‘barking’ with ‘dog’. The ear and the eye both bring messages to the brain but they arrive in different places and there is a temporal lapse before the brain can make complete sense of what the messages received ‘mean’ to it. There may be an even longer lapse if the specific input doesn’t quite fit the universal dog concept in your brain – a tiny squeaking lhasa apso causes cognitive dissonance with the large deep-voiced dog in your head and it takes a little longer to reconcile the little lapdog with ‘dog’. (There’s also a temporal lapse between what the brain then decides to do with the input and ‘you’ becoming aware of the thought, but that was discussed in an earlier post. You reach your hand to touch the little ratter wondering whether it might bite you, and then you are surprised when it does. Why didn’t you think of that before you put out your hand?) (And how many of you just thought of the old Inspector Clouseau scene of the encounter with a dog in the hotel lobby???)

Then along came language (well, actually, just words, language came later) to make this process of making sense of the world easier, perhaps. Language is a set of organized words and words is code for concepts and while this may facilitate comprehension of the world, language introduces an extra level of effort in the brain, as well as opportunity for error – the code does not always translate accurately into correct concepts in the brain.

Words – language – were spoken long before they were written. Words may have evolved 1,000,000 years ago, language 100,000 years ago, but it was oral; written language didn’t appear until perhaps 10,000 years ago, or perhaps only 3000 years ago. Words are a set of sounds and sounds are represented in written language by letters. Words existed before letters and Letters always represented the sound that had been associated with some object. The European Latin-based languages (as well the Greek and Cyrillic languages to a different degree) emerged from ancient Greek and Phoenician words. For example B derives from the Phoenician (and earlier Semitic languages) word bayt – house. (Curiously, none of the European languages have a word for house that sounds like bayt, or even starts with a ‘b’; the word didn’t survive, just the sound did. Even more curiously, house in Tagalog is bahay; Tagalog was not a written language until the Spanish came along.)

So objects, and concepts, were represented by sounds and sounds begat words, and words represented images. Images in turn were drawn on a surface and became letters. And letters/sounds in combination begat words that the eye could see, and these codes represented concepts that the mind already had learned. The codes are filed away in memory to be retrieved when needed, most of the time. And these codes greatly improved the ability for humans to communicate with one another.

But these codes are filed away in different places in the brain from the concepts they represent. And sometimes the brain has difficulty associating the codes with the concepts. This is not just a problem of dyslexia, wherein the codes are somehow scrambled; we all encounter coding conflicts at times. You’ve no doubt tried this little experiment:

The red house vs the red house

You read the word red and your mind almost instantly (to most of you) understands the colour red. But if the word red appears in green type on your screen, assuming you are not colour blind, you have a moment of cognitive dissonance.

If you are an auditory reader, that is, your ‘word concepts’ are stored predominantly in your auditory centres, your brain translates the visual word ‘codes’ into sound codes. You saw the word red but you might have not even thought of the colour at all but the act of reading. (He read the house quickly.) You may have ‘read’ the word ‘red’ and your brain sounded it out and comes up with book, or even room, meaning audience. (This is the problem with homonyms – they all sound the same – and writing the right word: there, their, and even they’re; new, knew, even gnu.)

I’ve now written almost a thousand words and I haven’t even begun to tell you about flow, or even Flo. (I know no Flo, nor even a Florence, so I have nothing to say on that matter, though I think Carmen’s cousin in London is called Flora.)

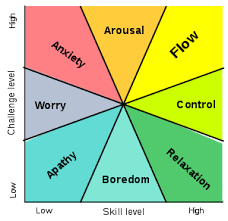

But I do know a bit about flow, and not just the lava kind, or the river kind, but the Mihaly Csiksgentmihalyi kind. When your mind (and the willing cooperation of your body) immerses itself in some activity intensely, all other thoughts and worries evaporate. This is MC’s formula for how to achieve periods of happiness and Martin Seligman agrees with him. But it takes effort.

My purpose in life is not necessarily to be happy so much as to be worry-free. Regardless, you can put yourself into that state by becoming absorbed whole heartedly in something. Some people can do this through ‘mindful’ meditation. I can’t. I have to do something. So I write. I’ve said my purpose is to be the best version of myself I can be, to utilize my talents (and virtues), especially if in doing so I can contribute to something larger than myself – the well-being of others. So I have determined that creativity, via writing, primarily, is the vehicle by which I can achieve my purpose.

Sounds so grand and high and mighty, doesn’t it? Makes you almost want to throw up. Why can’t Doug just content himself with being ordinary, not so bloody pretentious. Why can’t he just be his authentic self – ordinary, mediocre. (Who’s to say pretentiousness isn’t authentic?) Anyway, that’s not the point. The point is that I, at least, am not content to just ‘be’; I feel the need to ‘do’. And not just ‘do’, as some idle occupation to distract myself from the ordinary exigencies of life, but to do something just a bit stretchy for me, to be a better self, even if just a bit.

So I write. I write to allow my creativity to emerge. I write to give myself the chance to be better than my ordinary self. And perhaps make a small difference for others – to entertain, possibly to educate.

But who am I kidding. I also write for escape. When I am writing, when I am immersed in my writing, I am in flow. (And somewhere in my primordial male brain I might like to distract myself by being in Flo but let’s just leave that shall we?) I think about almost nothing else when I am in my writing state (though every once in a while the music on CBC, or the 11:00 o’clock news, will interrupt my thoughts) and all my cares and worries and frets melt away. I write to distract myself, and all those lofty other goals and purposes – to entertain, possibly to educate – are just justification, pretense for some higher purpose that may not actually be true. But I don’t care. I am in a good place when I am writing and I am in flow. (Although, that little self-doubting part of my brain speaks up and questions whether my writing is ‘good enough’. More on that rub in my next blog.)

This blog post is a case in point. I was going to post yet another article on Purpose and Signature Strengths and Values in Action and evaluating 2020 and plans for 2021 based on these concepts, but then I thought, readers are probably getting pretty bored with all that. After all, how much entertainment do they derive from such heavy stuff. Maybe I should write about what I’m actually doing these days, not just what I burden my thoughts with, and yours if you even read them. Instead, a little light education, and layer on a little humour. So I resolved to write about writing.

And I have already been rewarded in this, perhaps coincidently. I’ve spent many hours on this blog post, immersed in flow. Not that my days are filled with joy and bliss – you can’t stay in flow 8 – 12 hours straight – and when I’m not in flow my mind drifts back to the usual pattern of frustration and ennui, just like millions of others, their lives interrupted by our governments’ ineffectual efforts to save us all from ourselves, and the dreaded corona virus. But at least when I am writing I have temporary respite from my cares and woes and say bye bye blackbird.

So for two or three hours per day, often including weekends, I write. Until I immersed myself in this blog post, or should I say, became immersed (was it an act of will? Or am I just allowing myself to be swept along?) I would face my keyboard and screen and re-engage with my manuscript, The Treasure of Stella Bay. I must say the revisions I have made in R1 have not been nearly as satisfying and consuming as the first draft, but the daily effort nevertheless pulls me back to another time and place. Stella Bay circa 1961 is infinitely more pleasing than Bridlewood in 2021. Perhaps my writing is just escapism for me, and not the higher purpose I claim.

But I don’t think so. Quite randomly I had feedback from two of my readers last week about Travels With Myself. And these were not the usual suspects. One woman wrote me and told me that writing about the trials and grief I had gone through in 2018 must have been therapeutic for me. I don’t really agree with her – I thought I was just compelled to tell my story, not self-soothe – but she may have been right. Here’s what she had to say:

‘Travels with Myself has so far been quite enjoyable, [she’d just finished chapter 48] It’s caught me by surprise. As I read I am seeing this, Love of yourself is all you need, everything else falls in place.

‘I will enlighten you on the surprising factor: you have a unique persona of energy, I know this from seeing you in our office, not the grief-struck person in ‘Travels’. It’s no wonder your book is such a wonderful enlightening read, I am thankful for your courage; sharing your grief was your process of healing your heart. Be proud of the strength you have, Own it …you earned it.’

Now doesn’t that make your heart swell. Doesn’t that make me want to hasten to get back to my keyboard?

Another woman of my acquaintance reading TWM had this to say when I was talking to her last week: ‘I’m really enjoying your book. Even though I knew some of your story from our conversations the book has shown me so much more insight. It’s a pleasing read even though tough at times. You write the way you talk, it’s like you’re in my head talking to me.’

So writing, and having readers like what I write, has certainly helped me with my own struggles with life in the time of covid. I have been sleeping better in the last two weeks than I have in the last two years, or more likely the last twenty years. Maybe I am more content. Or maybe it’s the meds.

Now isn’t it interesting that you understood all this? You have been able to interpret 2000 words, 2000 bits of coded concepts? You should thank your mother. I thank mine.

Doug Jordan, reporting to you from Kanata Ontario

© Douglas Jordan & AFS Publishing

All rights reserved. No part of these blogs and newsletters may be reproduced without the express permission of the author and/or the publisher, except upon payment of a small royalty, 5¢.

[1]Even then, ability to speak and communicate did not necessarily explain consciousness. In fact one fascinating theory argues consciousness didn’t emerge until speech became written. Julian Jaynes, ‘The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind’.

[2]Now, don’t get me started on ‘I’. It’s hard enough to get your head around the dog concept, never mind the ‘you/I’ concept.