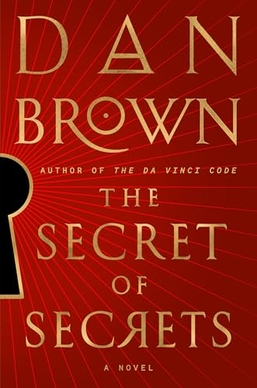

The Secret of Secrets. That’s the title of Dan Brown’s latest novel featuring the unlikely flamboyant adventures of ‘symbologist’ Robert Langford. And as titles go, it’s a pretty good one: It invites you to wonder what the book could be about? What are the secrets? And what secret holds other secrets? There are few hints on the cover to let you know – you need to read the book to find out – and that’s the whole point of a book title and cover.

Dan Brown is now a very well-known author, achieving the kind of recognition most aspiring authors seek. His second book, The Da Vinci Code sold millions and millions of copies and was made into a blockbuster Hollywood movie. This success made his first, largely overlooked, book, Demons and Dragons, a best seller too, and this led to four more Langdon books in the series, of which The Secret of Secrets is the latest.

Rating Brown’s Book

I confess, I enjoyed the Da Vinci Code, both book and movie, and that lead me to Demons and Dragons, which somehow did not have the grip and pace of Da Vinci Code. I never got around to reading the 3rd, 4thand 5th books in Brown’s series despite some intriguing precepts in the books: Why should a series about an unlikely protagonist, a Harvard academic, attract readers? Books with a heavy lading of historical information and obscure facts? Each of his books are well-researched, it appears, but why the widespread interest in Roman Catholic Church esoterica, historical references, architecture and symbology (whatever that is)?

Brown’s novels feature a compelling pace, multiple characters, mystery and intrigue. Short chapters, each ending with an irresistible invitation to read on.

But they can be annoying. Extremely unlikely premises, too many characters converging, a staccato-like pace bullying you to continue reading well past your bedtime lights out promise to yourself.

In Secrets a key theme is a theory of consciousness, and, despite my reservations, I was interested in what Brown had to say about it. Professor Langford’s main squeeze this episode is a neurologist named Dr. Katherine Solomon who has become a pioneer in the new science of ‘noetics’; she has postulated a theory that consciousness does not reside in the brain but in the universe; the brain is just a neurological receptor for signals that come from ‘out there’. And wouldn’t you know it, the CIA is very interested in this potentially powerful way to control the thoughts and behaviours of the presumed enemy.

Well I pretty much lost it at that point, but because of Brown’s compelling writing stye, I didn’t stop reading, just muttered a lot.

My review of The Secret of Secrets can be found on my Goodreads page here (or here[1]). Is it a four-star rater? (inventive plot, compelling writing, well-researched) or a two? (over-the-top cliché-ed plot, overbearing writing, lazy academic rigour). Even if I used my -5/+5 rating scale, I don’t know. Both/and perhaps.

Consciousness

What I really want to rant about though is the apparent preposterous premise of the noetics scholar and her theory of consciousness. And it is for this reason that I found Dan Brown’s swash-bucking novel offensive. He makes no serious attempt to clarify how or what causes consciousness to somehow reside in the universe nor give any evidence as to how the brain (presumably) tunes into the signals from the universe. The problem of consciousness deserves a whole lot more serious attention than the throwaway new-age ‘universe’ meme Brown gives us. Many serious scholars, scientists and thinkers have offered theories or ideas of what exactly is consciousness and how it comes about. No one has a final accepted answer.

Let me hasten to say that I have read a lot about consciousness – one of the four or five most crucial speculative questions human beings with their overactive brains have pondered: ‘what is the nature of the universe?’ How did it all begin? What is infinity (and beyond?) (How big is big, how small is small?)? Is there a god? Is there life after death? What is consciousness, really?

Let me also say that I don’t have an answer (though I do have a preferred view). It is highly probable that mere humans will never find the answer to these questions, unless, perhaps, there really is life after this life and god gives the newest arrivers all the answers then. (And the problem with that solution is that nobody has ever written home and let us terrestrials in on the secret.)

First, what is meant by consciousness? It is surprising how many of us have not given this a lot of attention – we just accept that we ‘are’ conscious and that’s it. The mind and the brain are simply accepted as one and the same thing. Consciousness is generally defined as ‘the state of being aware of and responsive to one’s surroundings’ (AHDOEL). But that’s not quite enough. For humans, consciousness is not just being aware of and responsive to one’s environment, it is the self-awareness that we are aware.

All zoological species have at least some perceptional ability to detect its surroundings and respond accordingly, especially if the phenomenon moves. Amoebas to alligators take in information through their senses and respond according to whatever meaning they apply to that perception; their motivations basically three simple things: danger (survival response, fight or flight), food, or sex. But there is no, or almost no, evidence that any of these animals have any self-awareness. Faithful readers who ever knew dogs realize that there is clearly something going on in the dog’s small brain, when it is awake (and maybe even when it is sleeping) – you can see him interact with his surroundings, sniffing eagerly in the corner of the yard, cocking her head in an inquiring way, coaxing you into throwing that tennis ball, or fishing for the treat hidden in your pocket. They have five senses, (or possibly six – How do dogs know when you are coming home[1]??); environmental information is passing through those receptors and on to their brains; the dog’s brain must then process the information and do something with it: fight, flight, eat it, fuck it or ignore it, mostly ignore it. But is the dog aware of its own thinking? Is it self-aware? Is it conscious?

Now, as a biological materialist, and evolutionist, my belief is that human doings are not much different from your typical standard poodles: We, our brains, take in data through our five senses, (or possibly six?), filter it in some fashion, compare the information to previously experienced information stored in memory, predict what is likely to happen next (as it has in the past) and act accordingly. And if that action didn’t produce the expected response, the brain feels surprise and makes adjustments, both to actions and to the stored information. The fittest amongst us – those with the physical attribute that produced the best response, and the mental ability to make the most accurate predictions more often than not, survived to reproduce and pass on their advantaged genes. And most of this takes place without us actually being aware of it, or least, before we became aware of it.

The answer to the question

In many ways the answer to the question of consciousness is simplicity itself. We humans are no more conscious than dogs, or even lobsters. (The answer to the question of how it all began, and by whom, is completely unanswerable.)

I said I was a biological materialist: What you see is pretty much what you get. We are mammals made of a couple of hundred pounds of atoms and molecules (mostly hydrogen, oxygen and carbon) and our brains (mostly fat and protein) run on glucose. That 3 ½ pound universe contains enough specialist nerve cells, and many more multiples of connections, to process a lot of information in very little time; it perceives environmental events, compares those events to previously perceived and remembered actions and ‘orders’ a response in nano-seconds, then stores the experience in memory. A brain is a biological organ performing certain tasks, just as all the other organs in our bodies have specially evolved to perform particular tasks. That’s it.

But this functionality doesn’t answer the question of why we think we are actually conscious, that we are simultaneously acting, and aware of ourselves acting, and doing so in real time. We believe our conscious minds are in control of our bodies and our actions, but there is plenty of evidence to show that neural activity in regions of the brain that control the action are active as much as hundreds of milliseconds before we actually become conscious of the action. In other words, the action precedes our awareness. And If the action preceded the awareness, what actually commanded the action? Moreover, where in the brain is this awareness occurring? Where is this thing we call a mind? Is it a homunculus in some sort of control room in charge of the rest of our bodies? Are ‘we’ actually in control of our thoughts and actions? or mere spectators in the theatre of our minds?

This 3 ½ pound lump of electro-chemical matter, and innocent arrogance, somehow asks the questions that may have no answers. And, for some, even asks the question: Am I conscious now?

Our complex and very fast brains create mental ‘concepts’ (images, sounds, smells, tastes, touch) of what it has perceived. It also has created a self-awareness concept of ‘itself’ and records the information in memory which is played back nanoseconds after the actual event. I think mind/consciousness is all illusion. But I could be wrong..

For Dan Brown to suggest, with no evidence, nor even attempt at explanation, that the brain is merely a signal receptor and acts on messages coming from beyond in some timeless instantaneous universe, is fraudulent and lazy. He may even be right. But we deserve better.

Doug Jordan, reporting to you from Kanata

© Douglas Jordan & AFS Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of these blogs and newsletters may be reproduced without the express permission of the author and/or the publisher, except upon payment of a small royalty, 5¢.

[1] This is a two star book – too long, convoluted, fraught with unrelenting action typical of Brown.

This is a five star book, fluid writing, fast-paced compelling narrative, practically impossible to put down.

This is many books in one: a thriller, a treatise on consciousness, an examination of mental health, a moral dilemma, an education of historical facts, and an amazing travelogue of Prague. Probably the last point is the most compelling: tourism to Prague will increase in the next few years.

[2] Rupert Sheldrake, The Sense of Being Stared At, and Other Unexplained Powers of the Mind, (2003)