10! She’s a ten.

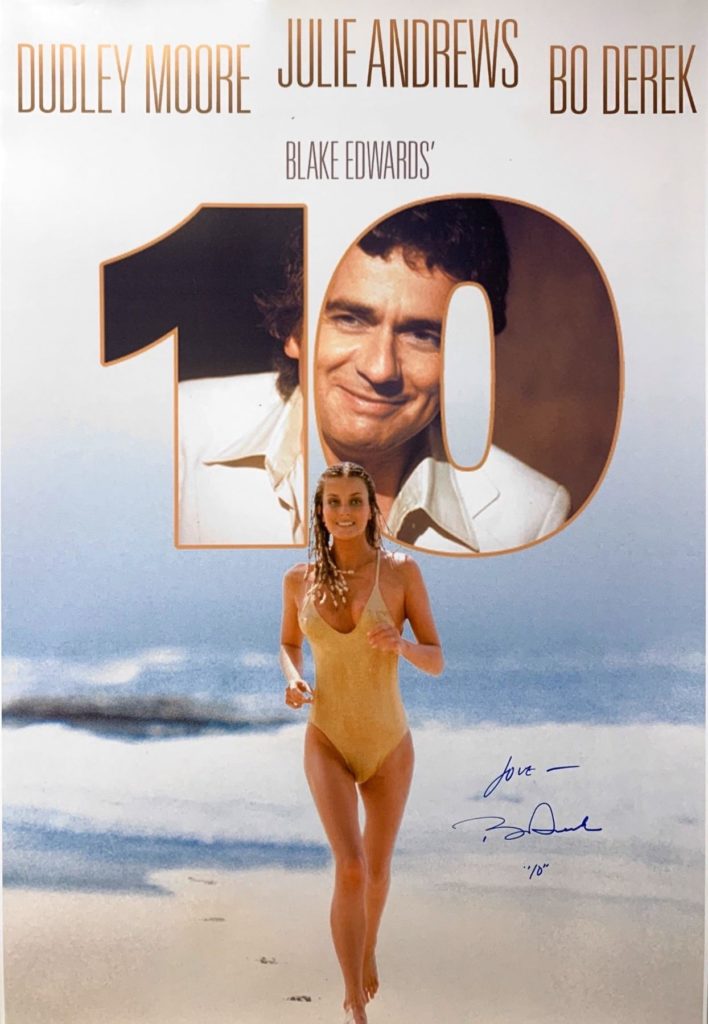

And everyone, well, almost everyone, knows exactly what that means: A beautiful woman. Bo Derek in the movie, 10:

Personally, I never thought Bo Derek was a ten but there you are.

Six, she scored a perfect six. And what do we mean here? Why, it’s the [former-day] Olympics: gymnastics, diving, figure skating, where 1 meant very poor and 6 meant outstanding[1]. But are they absolute or relative terms?

The film industry has two scales[2]: the five-star system used by most reviewers (and the general public) and the ‘Rotten Tomato’ score. (Paradoxically, a high % Rotten Tomato score depicts a highly praised film.)

Books are rated on a five-star system, but nobody knows what five stars actually means. Excellent, evidently, but how excellent? Many reviewers reserve ‘5’ for exceptionally positive and, perforce, will downgrade their otherwise strong positive rating to a four. If 4 is the default score for a highly regarded book, how can we know what 3 stars mean? or even fuzzier, what does one star mean? Most would intuit that a 1 means terrible, but if that is the case, why any star at all?

And for many reviewers, a five-point scale doesn’t give enough gradation: I gave that book 3 stars on Goodreads; I didn’t think it a 4 but there’s no 3½ on the five-star scale.

So what does 10 (or 6 or 5) really mean? Without a definition of the points on the scale it becomes completely subjective: the usefulness of a rating scale can be improved if a qualitative description is given with each point on the scale. For example, if the points 1-10 are given without description, some people may select 10 readily, whereas others may select the category rarely. If, instead, “10” is described as “near flawless”, the rating is more likely to mean the same thing to different raters. This applies to all categories – if they are well-defined – not just the extreme points.

I don’t know what sort of scale judges use in a book award competition. Maybe it’s like figure skating. I know that books competing for a big prize are reviewed by a panel of judges, themselves, presumably, accomplished writers/editors/reviewers. There is a set of criteria assessed: plot, flow, character development, and so on, and each criterion is evaluated and then a total assessment of the book as a whole is rated. The panel then comes together, compares ratings and notes, and argue amongst themselves until a winner is produced. But what scale is used? I believe it is the same 5-star system but without a clear rubric as to what 5, or 4 stars mean, we still don’t know whether the winner was an absolute excellent book or merely mediocre, the best of a poor lot. Even with relatively well-defined criteria we still have a subjective process going on – one person’s 5 could be another person’s 2.

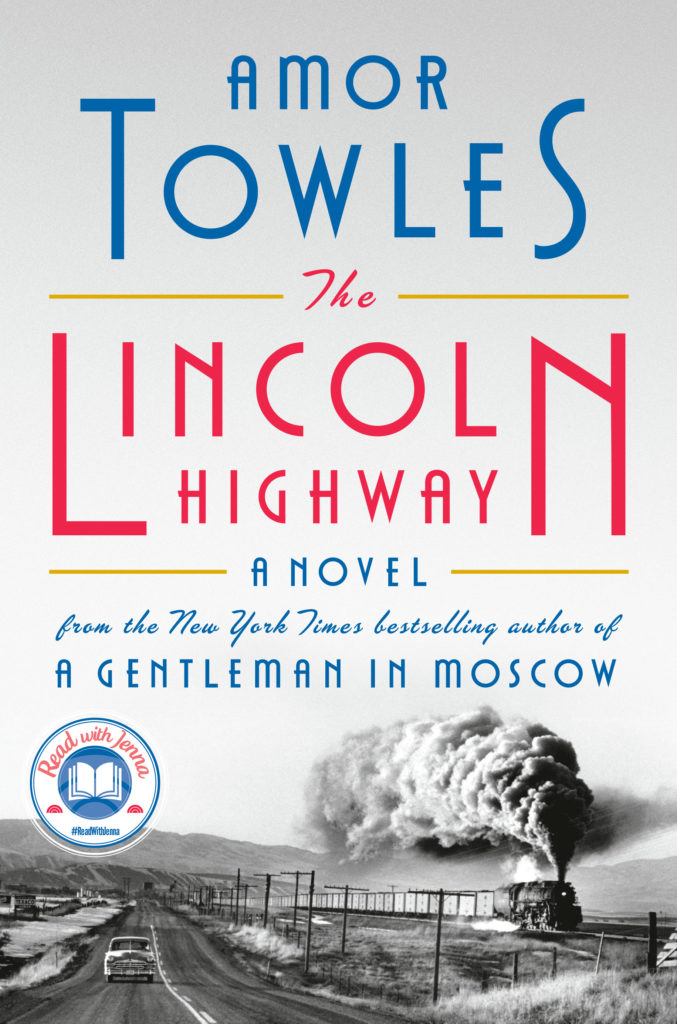

Look at any book widely reviewed on Goodreads. (I say widely reviewed so that we can have some sense of detachment from these reviewers – they’re not all family and friends trying to give the book a boost.) Here’s one: Amor Towles, The Lincoln Highway (one of my all-time favourite books (I gave it a five!)).

Community Reviews:

Overall average, 4.22; 303,919 ratings; 31,546 reviews

5 stars 136,972 (45%)

4 stars 111,398 (36%)

3 stars 43,748 (14%)

2 stars 9,265 (3%)

1 star 2,536 (<1%)

Wow, over 300,000 ratings! And 45%, like me, thought it a terrific book. On the other hand, 0.8% rated it 1 star, but that’s still 2500 people who, presumably, hated this book.

Compare these scores with my book, The Treasure of Stella Bay. Nine raters gave it an average score of 4.33; all 4s and 5s, none gave it only 1 star. Does this mean my book is better than Towles’?

Not likely. But in any event, unless they wrote a review to accompany their rating, we don’t know why these raters thought the book was ‘good’ – were they merely family and friends, not wishing to offend, or overly effusive in praise of my effort, if not the result?

I think these 5-Star rating scales for books and movies are fatally flawed and don’t provide objective ‘truthful’ information.

We need a scale where some sense of negative assessments (failure) factor into the ratings. We need some clarity around what does a five mean, and a three for that matter, but we certainly need to know what a 1 or 2 might mean: is that still a positive rating? What if the book is truly dreadful? Does it still get a 1?

As an active member of the Canadian Authors Association, as well as offering my services as a publisher/consultant helping other writers find their audience, I have been on the reviewer side of many books from aspiring and emerging writers; in most cases these books showed potential as stories but often lacked polish, even coherence; some are excellent and deserve to have a wider audience. As a life-long readers I have also read and reviewed hundreds of books from published authors whose works have survived the scrutiny of the publisher/editor. Often these are writers whose works have been on best-selling lists for months. And they are dreadful, and yet rated 5 stars by devoted followers. Being a published or ‘best-selling author is no guarantee that the book itself is any good.

So what to do?

We all experienced, I hope, the thrill, or agony, of getting our examination paper back from the teacher/examiner and frantically looking for our mark: pass or fail, superior or unsatisfactory; where 100 is perfect and 50 is a pass; 80 is superior and 30 is abject failure; now there’s a scale we can understand.

We need a scale that allows for ratings of superior quality as well as inferior quality. Both positive ratings as well as negative.

Social scientist pioneer, Rensis Likert, developed 5-point preference scale to try to measure positive response as well as negative: Not at all favourable, somewhat unfavourable, neutral (neither agree nor disagree), somewhat favourable, fully favourable. You can vary the terms but in all cases the scale needs to be balanced from negative to positive and the mid-point as neutral. The problem is, people often feel that a five point scale is too blunt, doesn’t provide enough nuance, and the neural score is perceived as empty, meaningless.

I propose an extended Rensis Scale for rating books ranging from the truly awful to the wonderfully crafted and entertaining. It needs to be an odd-numbered scale to allow for a central midpoint evaluation, but not neutral – the pass/fail threshold. It would need to be a sufficiently wide scale to allow for rater subtlety. Perhaps a seven-point scale, but more likely an 11-point scale to adapt raters used to tens, or fives.

Something like this:

- -5 Truly dreadful

- -4

- -3 Too many flaws

- -2

- -1 Slightly Unsatisfactory

- 0 Barely acceptable

- 1 some merit and potential

- 2

- 3 workmanlike competence

- 4

- 5 Exceptional Merit

(The 4s and 2s on this scale are left undefined for lack of sufficient vocabulary and to allow the rater to choose his/her own sense to the meaning. Maybe a seven-point scale is enough.)

With our eleven-point scale maybe now we can get some meaningfulness in rating books.

Doug Jordan, reporting to you from Kanata

© Douglas Jordan & AFS Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of these blogs and newsletters may be reproduced without the express permission of the author and/or the publisher, except upon payment of a small royalty, 5¢.

[1] But in fact the 6-point ranking process has been replaced with a complex 10-point achievement scale multiplied by a difficulty factor. We may not have known what 6 (or 10) meant before but, other than the judges themselves, we have no better idea now what a 9.7[1] means than a 6 previously, only that the person awarded that high score beat out all the other competitors for the gold medal. In today’s Olympic games, a modern Nadia Comaneci could never score a perfect 10.

[2] Well, actually there was a time when film reviewers Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert rated movies on a two-point scale, thumbs up or thumbs down, but Siskel and Ebert often didn’t’ agree themselves.