In our previous post on the problems the brain encounters in trying to retrieve the right word to convey the intended meaning we discovered there are many ways the brain can go wrong, and this goes beyond just the problem of homophones and homonyms. Here I want to dig a little deeper into this problem of how the brain processes, stores and recalls, and communicates, words, both from the sender and the receiver’s point of view. I doubt this article will make things much clearer.

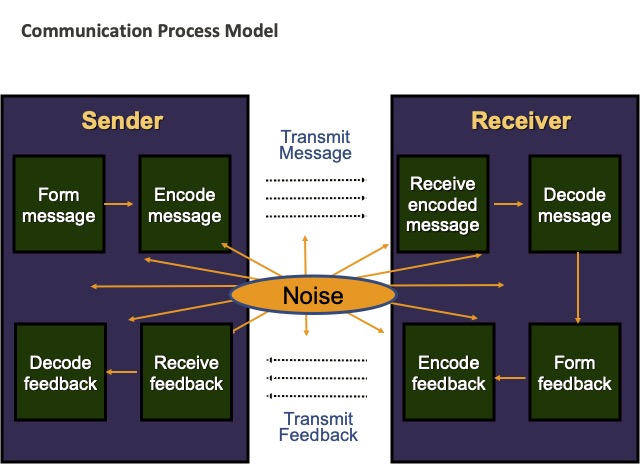

The classic communications model, below, shows where a message can go wrong between the sender and the receiver, and back again:

(With permission, Stephen McShane, Canadian Organization Behaviour, 6th ed., 2006, McGraw Hill Companies Inc.)

Or, to put it another way: ‘What you fail to understand is that the message you thought you heard was not the thought I intended to convey’.

Even if we take particular care to communicate what we fully intended – picking our way through the maze of our minds to find the right words, despite all the homophones and homonyms, synonyms and random misremembering that might trip us up – we have no control over the chaotic mass that may be the receiver’s brain, and so we are left in doubt whether the received message was actually understood as intended.

The receiver has to overcome any ‘noise’ that’s in the environment between her and the sender, receive the message accurately, whether visually or auditorily, and then decode it accurately. (And even if decoded accurately, comprehend it similarly to what the sender understood the code to mean.)

This problem is particularly evident in communications between two people who do not have the same language and experiences. The young French suiter says to his English beloved, ‘I zing you,’ intending his meaning to be ‘I sing to you’. But the surprised young lady looks at him, shocked, and says, ‘see you later, jerk.’ Hence the end of a beautiful relationship.

The Communications Process Model nicely maps out Murphy’s Law in communication but doesn’t explain what’s going on in the brains of the interlocutors giving rise to these errors. And in many ways, neuroscientists are still trying to understand the mysteries of the brain.

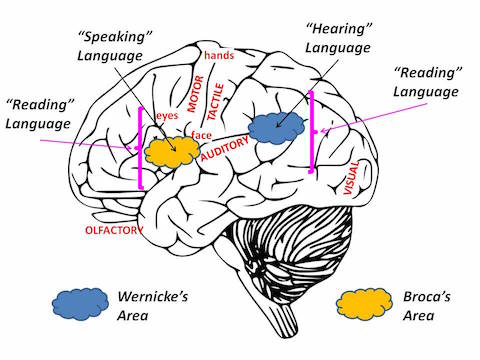

In our previous post (The Problem of Homophones) we were mostly talking about the obstacles the sender’s brain has in encoding the message he seeks to send. (Forming the message is another problem altogether!) In particular we offered that the brain files concepts and images in some parts of its vast synaptic web, and keeps the words for those concepts and images in other parts. We also argued that the brain may ‘think’ words as sounds (and stores them in the auditory areas of the brain) rather than as symbols (letters and words) which are stored in the visual sectors of the brain. (And we won’t get into the problem some have with synesthesia (seeing words in colour, or colour as words – yellow is butter – or smelling sounds), or the McGurk effect – ‘mishearing’ words by misreading lips.)

Language Centres of the Brain

While neuroscientists seem to understand that networks of neurons in the brain store images and sounds as some sort of electro-chemical pattern that replicates the original signals from the sensory receptors (eyes, ears, taste buds) it seems less clear how ‘letters’ and ‘words’ representing those stored electro-chemical patterns are produced and stored in the brain’s synaptic maze. It seems evident, for example, that the brain learned the concept of lion and recognizes when one is encountered, and it follows that primitive man produced sounds that also represented the lion, and so began a ‘word’ for lion to be conveyed to other members of his tribe. We can postulate how the concept of lion is held in neuronal memory but how is the ‘word’ lion held in memory? We understand that as humans developed language, (and later learned how to write it down (and how to ‘spell’)) letters and words are coded symbols representing thoughts. But how those abstract symbols – words – are stored, and retrieved, is still somewhat of a mystery. (Though, really, what can be more abstract than the neural electro-chemical pattern of the concept of lion?)

Regardless of the mysteries of the brain itself, in order to communicate, the speaker has to collect his thoughts, retrieve the ‘codes’ for his thoughts (words (auditory sounds)), and transmit that coded thought to another person. The receiving person has to be able to extract that set of coded concepts from any surrounding ‘noise’, decode it, and make sense of the concepts in the same fashion as the sender did: ‘Hey, look out! Lion.’ All of this happens in nanoseconds and the people communicating with one another are not conscious of what went on in their own minds. Miraculous.

Speaking is one thing, writing is something else again. With writing, at least, we usually have more time to compose our messages than when we speak, but, there is yet another layer of complexity in writing. We know the speech centre and the writing centre are located in different places in the brain. When you want to say something, does the speech centre explore the recesses of the brain to find the concepts, assemble the thoughts, locate and select the words, and transmit the coded message, orally? When you want to write something, does the writing centre do the same thing, but visually? If the thoughts/concepts are scattered throughout the brain, where are the words located? with the concepts? or somewhere else? Is there a dictionary? And are there actually two dictionaries?: A dictionary for spoken words and another for written ones, coded differently?

It’s a wonder anything gets said at all. At least now we can appreciate why at times we can’t find the words, we get tongue-tied, and we have writer’s block.

And all of that has to be repeated in reverse at the receiver’s end: she hears or reads the words, takes them into the speech or writing centres, decodes them accurately to the thought concepts and comprehends the message (and acts on it, or not). ‘Danger, lion ahead.’

Is it any wonder that the problem here is a failure to communicate!

This confusion is not just in the domain of the neuro-psychologists, nor is it a new phenomenon; for a literary person, (say, an author), or English major, there are even names for these slips: differentiation, malapropisms, not to mention homophones and homonyms. The English language has evolved and added so many words, it’s a wonder the feeble brain of the sender can find the right one at all, or the receiver to understand what the devil he meant by that word.

And this gives rise to the particular problem of homophones in writing: the auditory brain has no confusion over words that are different but sound alike, because context makes the difference but to the visual brain ‘misspelled’ (or mistyped) same sounding words, can cause confusion in the mind of the receiver of the message.

But selecting the correct word can involve more problems for the brain than searching for the right ‘sound’. It also has to search through its synaptic library for the right concept too. Since the brain ‘remembers’ words (and Names) by linking associated concepts it can make mistakes in finding the correct word by going down the wrong synaptic pathway of an erroneous associative concept. (Phew, that was a complicated sentence.)

This is the problem of ‘mis-association’: in searching for a word the brain ventures down two (or more) associative pathways, which may share some similar concepts or cues, but at the last instant, takes a wrong turn. Names, that is, formal Names, names for things starting with a capital letter, like Doug and Budapest, are particularly prone to these mis-associations, or worse, lead to a dead-end. ‘Names’ are stored uniquely in particular, likely more remote, parts of the brain but because the associative links for that specific word are limited, the brain has difficulty retrieving it, or, at least, recall it quickly, and often enough fails altogether. (This may be contrasted with frequently used words for which the synapses have many well-traveled associative pathways.) The Name is there, somewhere, but the synaptic path to find it becomes narrower and narrower. Here are some classic examples of the problem of obscure synaptic pathways inhibiting recall, possibly more common for men than for women.

I can find my way around my neighbourhood no problem; I can find my way across town if I’ve been there before and find my way home again. But when asked to say what the streets are called on these routes, I may draw blanks. I can lead you to a particular place, or draw you a map, with landmarks, but I may not be able to tell you the names of the streets.

Here’s another example, perhaps more particular to my time in Human Resources recruiting, or coaching. When I see someone from my past I may recognize that I know the person, and I can tell you a lot about her history, and career resumé, but I can’t recall her name. (Sometimes the Name hovers at the edge of awareness but my brain doesn’t quite trust itself and the Name sits ‘at the tip of my tongue’.)

This also happens in reverse. You could say to your colleague at a cocktail party, ‘you remember Mary Anne’, (someone you both once knew well but it’s been a while), and your partner looks at you blankly (‘I don’t remember a Mary Anne, or even maryanne?’). You then begin to provide bits of Mary Anne’s history and as you fill in the picture your interlocutor begins to realize who you’re talking about. By offering associative information you are helping the other party navigate his synaptic pathways to unlock his memory of that person. (If Mary Anne is actually present the effort to retrieve her identity can be a little awkward.)

Here are a couple more examples of confused retrieval of words – the problem of the jumbled synaptic pathways. These are personal examples, possibly unique to me, or a sign that my ganglia are become decayed or plaque-infested: The confusion between Valentine’s Day and Halloween; daffodils and dandelions.

(Please give me the benefit of the doubt here. It’s not that my brain is deteriorating, I hope, it’s just that it is getting overloaded with too many bits – the hard drive is full and the processor has to work harder to find what it’s looking for. Or, that’s what we oldsters tell ourselves. But yes, I worry if something neurological is off in this corroding, aging, brain of mine.)

So what’s the link that causes me to mis-name Valentine’s Day as Halloween? Why, chocolate, of course, especially as it’s a special occasion associated with giving someone chocolate. The listener may be surprised by my conflation of Hearts with Trick or Treats but she makes her own association in her brain, and, with a raised eye-brow, says: ‘Oh, you mean Easter!’

But daffodils with dandelions? Sure: yellow flowers blooming in spring, both beginning with the letter ‘d’. My conversation partner may have more difficulty interpreting that one. And may be thinking I need to make an appointment with my doctor and take a memory test.

Doug Jordan, reporting to you from Kanata

© Douglas Jordan & AFS Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of these blogs and newsletters may be reproduced without the express permission of the author and/or the publisher, except upon payment of a small royalty, 5¢.