Have you ever misspelled ‘there’, when you meant ‘their’?

Or ‘your’ when you meant to type ‘you’re’?

Of course you have. It’s a common problem.

It’s usually not a matter of misspelling, exactly, it’s more like mistyping. You know how to spell ‘they’re’ when you mean ‘they’re’, but somehow their shows up.

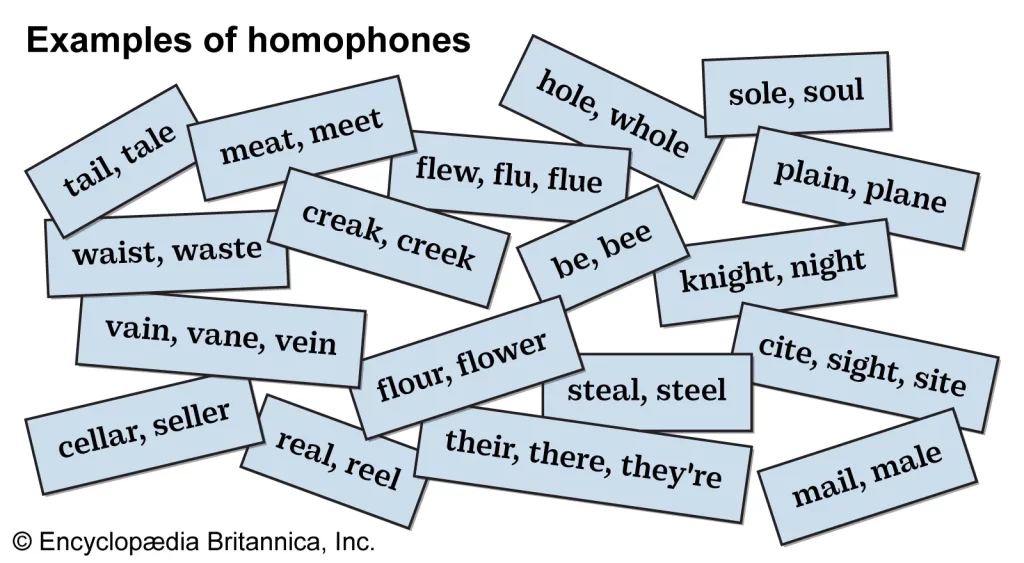

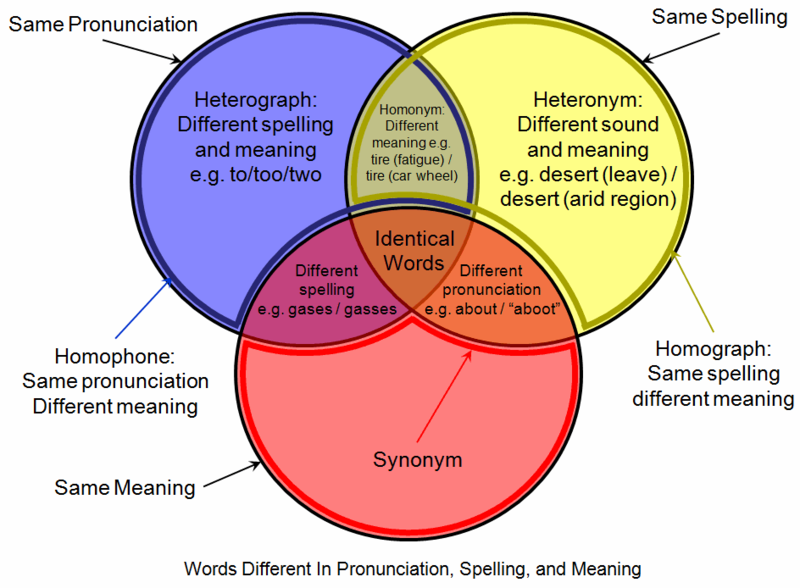

Homophones are words that sound the same but are spelled differently. And mean something completely different.

If you don’t pay close attention, a misplaced homophone can lead to difficulties, embarrassment, apologies. Particularly so if you consider yourself an accomplished writer. If you have been taught how to read and write, you probably learned the distinction between where from wear. Somewhere along the line – Grade Six maybe – you were even taught about homophones, (along with homonyms, synonyms and antonyms), and to take care not to mistake them. These were challenging concepts, but to 11-year-old boys homophones (and homonyms) were especially noteworthy.

Some homophones are sufficiently irregular in usage that we rarely mistype them. ‘You should check your cheques before you mail them’. (That particular problem has largely been fixed in modern (North American anyway) usage: most Canadians these days have adopted American English spellings and don’t use ‘cheque’ anymore – the homophone cheque/check has become a homonym ‘check’. For that matter, with internet banking, who even writes cheques anymore?)

But ordinary everyday homophones often, unintentionally, get misplaced. How does that happen? Usually you notice a mistyped word right away and fix it, or at least fix it in the second review of your message before you press send. But if you’re in a hurry and give only a cursory scan of your text you press ‘Send’ and feel more the fool after. Such a waist of time.

Of course we blame autocorrect for the error – we couldn’t have made such a simple mistake.

But on more reflection, we realize we made the error ourselves. We may wonder how that actually happened, even may begin to doubt our mental functioning.

I’ve long had a fascination for how the brain (mind?) works – that mysterious process of how we take in information, compare it with previously experienced things, make a decision, and act, or not.

Now we add language to the mix and wonder how the ‘mind’ deals with abstract things called words.

I’ve long had a fascination with words. Clever words, obscure words, onomatopoeic words, derivation, etymology, evolving words, misuse of words. I suppose it’s natural when you develop an academic interest in language, especially written language – I am a writer after all. Maybe I should have taken up etymology as a profession but I doubt there’s much work for etymologists. (Damn few prosperous writers too for that matter.)

I say ‘written language’ deliberately because it is different from oral language. Spoken language still depends on words, but not spelling. People have been communicating orally for thousands of years, and likely communicating physically for a million, but written language is relatively recent. (By physically1 I mean communicating by acting, pointing, demonstrating, grunting, emoting, facial expression; communicating without words.)

I doubt primitive man had problems with homophones.

Words are stored in memory along with everything else we experience in life. It was thought once that memory was stored in a particular part of the brain. But memory is not just in one place, and learned words and remembered experiences are not in the same place. Neuroscience now suggests memory is spattered (I mean scattered – why did I type spattered instead of scattered? the p and the c are not even close on the keyboard so I can’t blame the errant finger, this time); memory is dispersed all over the brain. Most of our lived memory is stored as images because they were experienced, for the most part, visually. But words are artificial constructs representing an object, or concept. Words are not ‘remembered’ as experiences are but are learned. Words are symbols, code even, for the idea. Letters (I’m speaking here of Latin-based languages) are also symbols originally representing some object and evolved into wider application because the symbol came to represent the sound not the object. The letter b, for example, in early Phoenician, is derived from the ‘word’ beth (house) and gradually came to represent the [soft] ‘b’ sound.

The key here is that language has been oral long before it became verbal, i.e., written. Written language (logographs, cuneiform, hieroglyphics) only began to emerge about 7 to 10,000 years ago, and phonetic writing (ah, those Phoenicians again) perhaps only 3,000 years ago. Human history was mostly oral until people began to write it down, and read it for themselves. The Iliad probably happened hundreds of years before Homer finally transcribed it.

So language is more an oral function than visual and it may be that the sounds of the words we speak (and hear) are located in different parts of our brains from the visual images they represent, or even the ‘words’ themselves. (Who knows where concepts and ideas come from or are stored?) Information is stored all over the brain. So when you want to recall something, and transmit it, your brain is searching throughout its vast network of neural pathways for all the images, words and sounds it has stored away and select which of those is needed to be transmitted.

It also turns out that synaptic pathways are stronger between neurons storing frequently used memories than obscure experience. The brain retrieves words associatively. Commonly used words are retrieved because there are numerous neural pathways to them. Words less frequently used – and ‘named’ things, i.e., words with capital letters, like Homer, and Azerbaijan – are stored with fewer bits, or only one bit, of associative information, and the neural ‘search engine’ struggles to locate the desired word. That’s why you have trouble recalling your distant Aunt Milly’s name.

It’s even more difficult to retrieve a name when you are in a stressful situation: you’re at a wedding or funeral and you have to introduce your Aunt Milly to your new girlfriend, and, under pressure to perform, you can’t recall her name – either Aunt Milly’s, or the girlfriend’s; it can be rather awkward. The reason for this difficulty is that anxiety tends to hijack normal neurological functioning. Emotions have no vocabulary, just action. (You know, action ‘speaks’ louder than words…)

So, recalling words is more difficult than we at first imagine. In spoken language, words that are different but sound the same are understood correctly in the context in which they are spoken. In written language it becomes necessary to know how to spell. If our brains store oral language in one place, and written language in another you begin to appreciate why our beavering brains, probing its auditory memory for the words, mistake their for there (or even they’re) while typing. The auditory brain of the speaker pronounces the word intended and the receiver ‘hears’ the spoken word the speaker meant; but the visual brain of the writer may fail to select the word with correct spelling: it fails to right write.

You, the writer, know which word you intended to use. But somehow your brain sent instructions to your fingers to strike the ‘wrong’ keys on the keyboard.

It isn’t just homophonic confusion that leads to incorrect word recall. Associative memory can also lead us down the wrong track. If synapses are tracking the neural pathways to the right word but have choices as to which associative memory is correct it may take the road more traveled than the side road, and that can make all the difference. (Apologies to Robert Frost.) This happens very quickly of course and the error is out before the mind can stop it. In speaking we may rescue ourselves by correcting, stumbling and stuttering. In writing we have more time to get it right but we need to proofread before sending, even if you have autocorrect turned on, or maybe especially. (More on this phenomenon in the next post.)

This post came about only a few days ago when one of my readers reported an error in Alex’ Choice. I have expected typographic errors lurk in the manuscript despite editing through multiple drafts, proof reading, and inviting commentary from trusted beta readers. One or two are bound to get through. After the fact we discover the errors and grimace; we can keep track of them and resolve to correct them someday; should it be a glaring error it becomes necessary to revise the online version and republish the book. (Another advantage of print-on-demand self-publishing.) But most of those typographical errors, missing articles, misplaced punctuations, mistyped homophones, can wait.

However, in the instant case, this was such an egregious error I probably shall not wait long to correct it.

But how did this error occur? And even more curious, how has this error been missed by so many readers? Maybe it wasn’t missed – the readers were just too polite and chose not to let me know. Or maybe the reference was sufficiently obscure, especially to younger readers, that many didn’t realize it was actually a mistake. But to me and my strained synapses, it is clearly a problem of homophones.

Young Alex, stressed with doubt about the affections of his love, decides, against better judgment, to take a bus from Kingston to surprise Sandra at the Nurses Residence in Toronto. He takes with him for solace a copy of Kahlil Gibran’s The Profit.

Did you notice the error this time? This famous book by the esteemed Lebanese poet and philosopher of the last century was not, of course, The Profit, but, The Prophet.

Perhaps no-one but the most literate, and astute, will have noticed, but, embarrassed, I am compelled to correct this synaptic lapse.

That leaves the problem of what to do about the 50+ copies of the book already in the hands of readers? I suppose, like rare stamps, their value increases by their scarcity.

Doug Jordan, reporting to you from Kanata

© Douglas Jordan & AFS Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of these blogs and newsletters may be reproduced without the express permission of the author and/or the publisher, except upon payment of a small royalty, 5¢.

- Sign language is a special case – it’s physical language but the actions represent whole words or letters spelling out the words. ↩︎