Humour, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. What’s marvellous to one person is base to another, and perhaps incomprehensible to someone else. Writers seeking to include humour in their writing ought to keep that in mind: to paraphrase Abe Lincoln – you can’t amuse all the people all of the time.

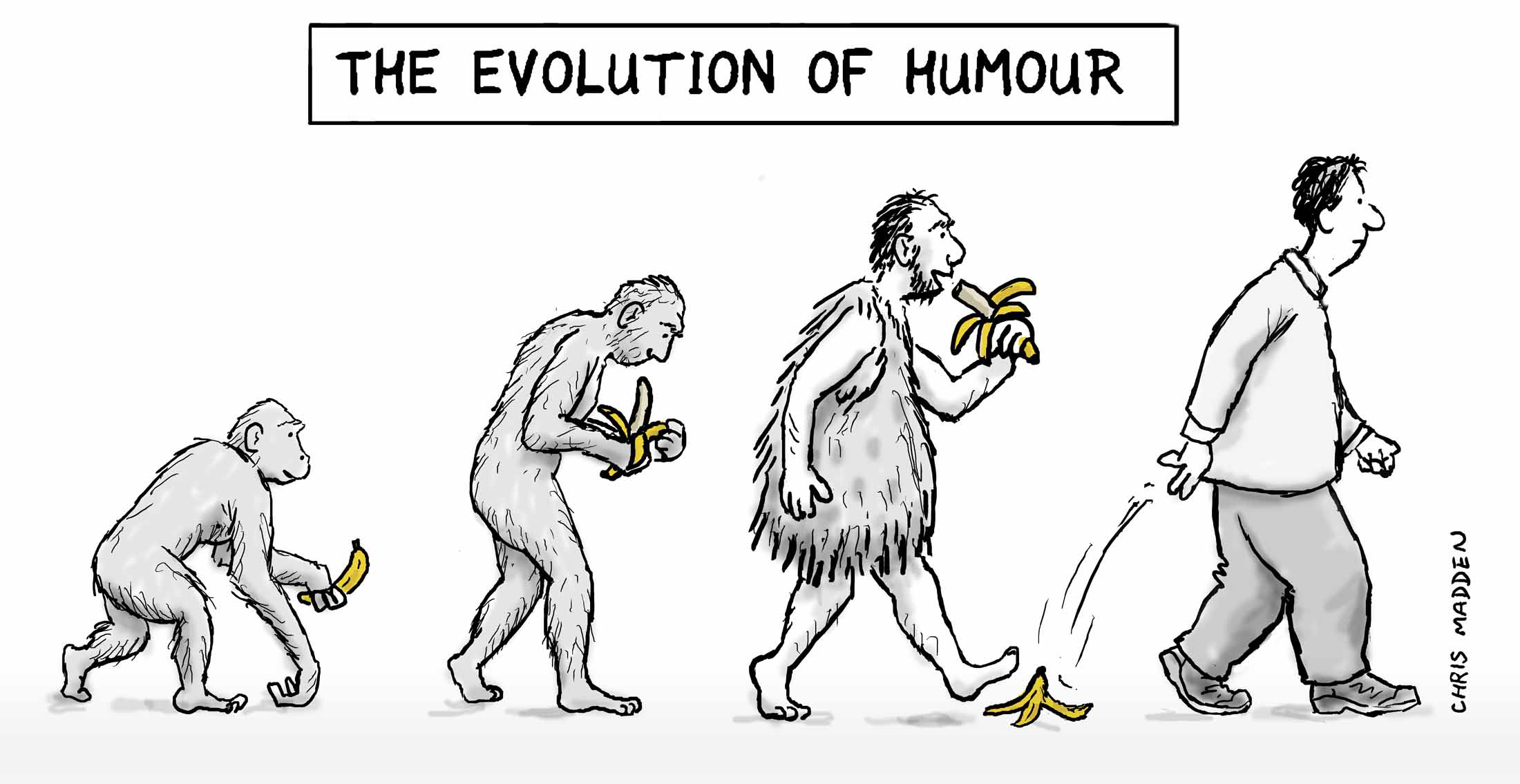

Humour tends to occur more readily in dynamic, live, social situations – conversations around the dinner table, or the conference table, if you dare; we laugh, or cringe, at stand-up comics, live or video. I wonder if comedy is accessed more readily by the auditory parts of our brains than the visual. Most physical comedy – that which you see rather than hear – is much less subtle, more pratfall, embarrassments at some victim’s expense. Really, what’s funny about seeing somebody slipping on a banana peel, or somebody being frightened by a person, dressed as a gorilla, jumping out from behind a door? Still, it is the surprise element, or perhaps the incongruity, that brings about the laugh. The unexpected that tricks the brain.

Reading (and for that matter, writing) is largely a solitary activity, whereas manifest humour may be more a matter of social contagion. You may be amused by something you read but to laugh out loud while sitting solitary in your reading place is rare. (Indeed, we signal to others that we found something we just read humourous[1] through the use of emojis (😅) or memes (LOL, LMAO).)

Physiologically the brain may not be ‘amused’ at all; consternated maybe, but not amused. ‘Funny’ may not be a neurological thing, only a subjective thing.

Neuropsychologist, Elizabeth Feldman Barrett (of whom I have written previously on the subject of consciousness) offers the thesis that the brain is merely a predictive organ (and may not be ‘conscious’ at all); it’s purpose is to take in data, continuously sorting and evaluating it by comparing to similar information stored in memory, and from that memory, ‘predicts’ what is likely to happen next. It prepares itself for action, or not. So when the next input is not what was expected the brain becomes confused, stressed, even alarmed (fight or flight), but in any event may express itself in surprise – i.e., laugh, or gasp, startle or react in some spontaneous, involuntary way. If the synaptic brain is slow to make a connection, or lacks the reference points in language or experience, there is no surprise, and that’s not something to laugh about.

The brain’s response occurs before the conscious mind is even aware that something ‘funny’ has happened. If your brain is very fast you may be laughing before others have got the joke. Or maybe you’re the only one who thought it funny. How embarrassing.

If humour comes about because the brain is surprised, how does a writer surprise his reader enough to cause him or her to laugh? (or at least smile to himself)? Writing well is hard enough, but to write something funny is seriously difficult. Indeed, much of the humour we see on paper or screen, is often cartoon-assisted text – the image complements or accelerates the words, or vice versa. And even much of that will depend on the mind of the reader (see opening sentence above.) Writing is hard because language is imprecise: the job of the writer is to accurately convey what he (or she) intended in his writing – the writer has to hope the reader understands the words the same way as he did. Writing humour may depend on the reader understanding the twist in meaning the writer intended.

Humour may also depend on timing. Humour seems to be a trick that’s played on the innocent brain. It’s the spontaneous, immediate reaction of the person perceiving the event; if the penny drops too late, it’s no longer funny. When you read something (whether slow or fast), your brain may have too much time (or not enough!) to think about the quip or the joke, or miss it altogether. The surprise factor is neutralized and the brain is not amused.

So how does the writer create the scene, and then the surprise, that gets the reader to laugh? My friend Terry Fallis, an author who produces humourous works (is that actually a genre?) has twice (or is it thrice?) won the Stephen Leacock Award for Humour and most of his books I have read were actually good yarns as well as funny. Terry recently ran a workshop for Canadian Authors giving would-be humourists some pointers on how to include humour in their writing. He made a number of interesting points, but I was left with the impression that reducing humourous writing to the abstract is academically interesting but may not help the wooden would-be humourist become a humourous writer. Humour in writing may be instinctive.

I’m a funny guy, or at least, many people have told me that. (And the ones that don’t find me funny, well, that’s their problem.) I’m quick with words and express the irony, or the double meaning, witty non sequiturs, in my conversation that catch people up; well, maybe not all of them, only the ones paying attention, synapses at the ready. Truth be told, many people are not good listeners – they’re thinking about something else, or what they are going to say themselves, witty or otherwise. And I’m not funny all the time. I need to be at ease, yet my brain alert, and in good humour myself, my brain popping along, unbidden by me.

(But, on the other hand, I’m not particularly good at telling jokes. To tell a good joke, (or perhaps I should say, to tell a joke well) the audience has to be in the right frame of mind – i.e., ready to be amused – and they need to hear the story told at the right pace, with enough character to draw the listener in, and then, wham, the surprise, the ending that wasn’t expected, the punch line that gave a whole other meaning to the tale that was being spun. I’m too impatient for that, I tend to rush my delivery, and even stumble over the punch line. People smile politely. You need to be an actor, an unrushed deliverer of the lines.)

My writing also contains a fair amount of humour. I don’t write humour for its own sake, deliberately writing a humourous story; I simply drop ironic or witty lines into the prose that seems a perfectly natural part of the narrative. You may have noticed some wit in many of my previous posts (or maybe not – you may not have found anything humourous there (pity) or you don’t read my posts, double pity. (So, what are you doing here now? Just visiting?)

Humour may also be an indicator of character type and so the writer can use humour (or lack of same) to flesh out differences in the characters. A humourous character will deliver witty lines or remarks from time to time, confirming his fun-loving attitude; a serious character is straight laced, purposeful, direct; if the writer gives his serious character a funny line it will seem out of character. It may be surprising, and even funny, but the reader will think it odd. Or hilarious.

The main characters in Alex’ Choice, and The Treasure of Stella Bay may be a case in point: Alex’ father, the cerebral Dr. Peter Jurgenson, professor of psychology with a particular interest in humour, the what and why of it, is a funny and sardonic guy, much to the annoyance of his wife, the serious and practical Victoria, who is not amused, and to the frequent confusion of son Alex.

Something is humourous to the brain because of the surprise factor. The unexpected words or actions somehow tickle the synapses and you laugh, or at least smile. But if your synapses didn’t get tickled, you don’t. If the book you’re reading makes you laugh, the writer did a good job. Or maybe the credit goes to you for finding it funny. And hopefully, that’s what he intended.

Doug Jordan, reporting to you from Kanata

© Douglas Jordan & AFS Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of these blogs and newsletters may be reproduced without the express permission of the author and/or the publisher, except upon payment of a small royalty, 5¢.

[1] You’ll probably notice that I misspell ‘humourous’ throughout this essay. All the dictionaries, even Oxford, advise that humorous is not an Americanism (inspired by Noah Webster) but an original English spelling. I have my doubts, Balderdash. I think somebody just got lazy and everybody thought dropping the ‘u’ efficient, or doubted themselves and didn’t want to be laughed at. I defend my erroneous ways vigourously.