‘If a thing is worth doing, it’s worth doing badly.’ (G.K. Chesterton)

I saw this quote recently in a Substack post (about writing, naturally – and I wish I could remember where I saw it so I could properly attribute it) and it struck me as wrong. Certainly it runs against conventional wisdom (I can hear my mother’s voice ringing in my ear): If a thing is worth doing, it’s worth doing well.

But then I thought, after a little reflection, not just kneejerk rejection, that may not be so wrong after all. And since Chesterton, genius writer of the last century, originally said it, I should investigate what he had in mind. But before I do that, first I’d offer my own thoughts, as an author, and former HR executive, on the problem of Quality, which surely Chesterton was getting at…

The concept of quality, and its derivatives – poorly, well, good, badly, worth doing – are largely subjective, and as such there is a certain relativism in the terms.

In common understanding, ‘quality’ is seen as a synonym for ‘good’, or high (highest?) standards. But if ‘good’ is a subjective term then ‘quality’ should also be seen as subjective, or at least relative.

I remember when I was VP Human Resources at Mitel Corporation, late in the last century, we embarked on a quality improvement campaign and worked to embed notions of quality into the culture of the corporation. It wasn’t just a matter of producing quality products, it was a matter of every employee taking quality for their own work seriously. So we sent a whole legion of employees on Quality Effectiveness training so that they could come back from their training and become internal trainers for all the rest of the employees. And evangelists for quality also.

There were a number of quality gurus wandering the world at that time promoting their version of quality and flogging it in consulting and seminars to manufacturing companies world-wide. The leading apostle at the time was Joseph Juran, who emphasized statistical sampling as a quality control method; his methods, largely shunned in North America, was adopted hook, line and sinker by the Japanese as they rebuilt their economy after WWII, and in time, Japanese car manufacturers began to take market share from the big four American manufacturers, if not ultimately eat their lunch.

(How many of you today drive GM or Ford cars? Who the devil is Stellantis? And whatever happened to American Motors?)

Mitel didn’t hire Juran, but opted instead for Philip Crosby, former VP Quality for ITT Corporation before he took his quality notions to the consulting market; there was merit in Mitel selecting Crosby over Juran because he emphasized culture change as central to instilling quality in the products (and services) of an organization, not just engineering standards.

Still, the abiding message coming from the Crosby School of Quality was this: Quality is meeting customer requirements. This was a revelation. Quality wasn’t about excellence, or goodness – subjective terms – but about getting as much clarity as possible about the customers’ requirements (and maybe even his expectations) and then getting agreement on what those requirements truly meant. Making these requirements as explicit and as definable, and measurable (though not through statistical sampling!), as possible. It wasn’t about measuring a ball-bearing’s diameter and circumference to the micron, it was about making sure that a micron was what the customer really needed (or wanted) and then delivering that product to specification. Part of the agreement is for the supplier to evaluate their own capability and make sure they had the capacity to deliver a product or service to the customer’s expectations. Transactions often run on the rocks from over-promising and under-delivering. The opposite is also potentially fatal, under-promising and over-delivering. What quality is about (according to Philip Crosby) is : promising, and delivering to expectations.

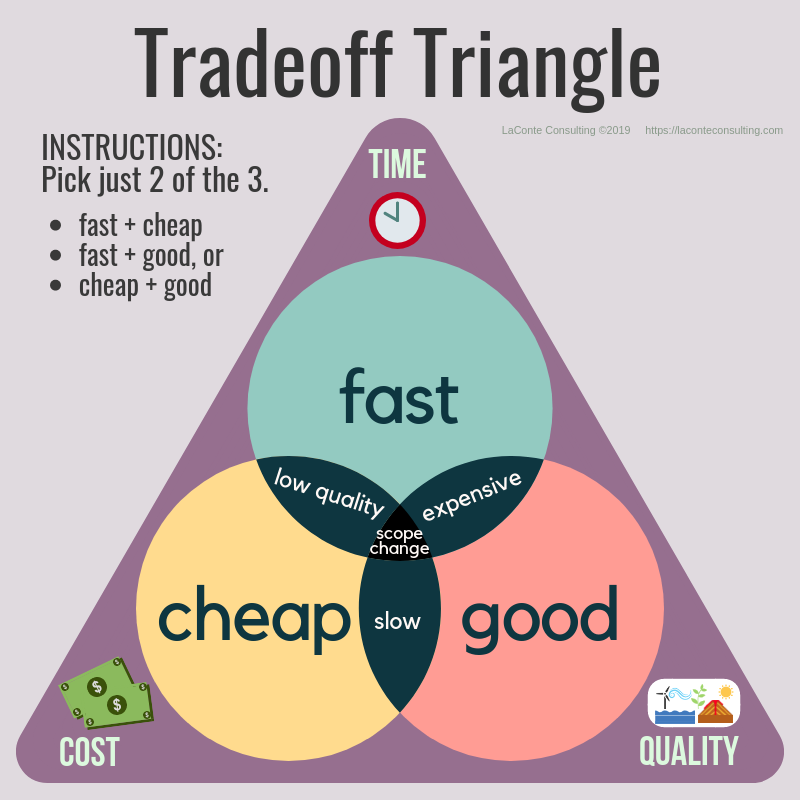

Related to this concept of quality, and central to the negotiations of requirements between supplier and customer, is the natural tension between three competing qualities: Fast, Good, and Cheap. This is often depicted as three points of a triangle:

You can have it fast, you can have it good, or you can have it cheap, but you can’t have all three. If you want it fast, and you want it good, it’s not going to be cheap. The customer has to choose which of these core criteria is preferred and the supplier has to decide if this is the market space they want to be in. There’s nothing wrong in having a product made of cheap plastic made in the millions but don’t expect it to perform like a highly refined stainless-steel item. If you can produce that cheap plastic toy to a standard higher than the customer expected, and you can still make a profit margin that meets your own criteria for success, then the customer may (only may) be delighted that you exceeded his requirements (but maybe not).

In other words, you don’t expect a Kia to have the refinement and durability of a Mercedes when paying half the price of the Kia, but you’ll be delighted if the Kia delivers features you hadn’t expected for the price. On the other hand, the Mercedes may disappoint if it fails to meet standards of fit and finish you expected in a car twice the price of the Kia.

If your business is to produce cheap plastic toys – and your customers only require cheap plastic toys – and you deliver cheap plastic toys reliably, you’re seen as a quality manufacturer of cheap plastic toys. This manufacturer, and its employees, have not fallen into the subjective ‘quality’ trap – trying to produce a better product than the customer actually needs.

So this is what Philip Crosby meant by quality as meeting customers’ requirements. It wasn’t about ‘goodness’.

A related notion, one most of you are familiar with, ‘don’t let perfection be the enemy of the good’. In the first place, the problem with this notion of perfection is that perfection is an impossibility. It can’t be achieved. You might be able to come asymptotically close but never arrive at perfection. Perfection is an abstraction, and perhaps, like beauty, in the eye of the beholder. More importantly, if the customer (and especially if you yourself are ‘the customer’) understands what his own standards of performance/deliverable are, they should be delighted when those standards are met, even though they may not be ‘perfect’.

On the other hand, if the culture of an organization, or even the value set of an individual, is to shrug and deliver whatever it can, even if it doesn’t meet the customers’ requirements, then the organization does not have a quality culture and eventually will lose customers. ‘Good enough’ is also the enemy of the good.

You may recall some of my earlier writings on life’s purpose: to be the best version of yourself you can be; to know your strengths and key talents and skills and take on projects where you can utilize these talents, and when possible to choose projects that benefit others (the altruism meme). (The bonus is that when you become immersed in your projects (flow) you derive a few hours of ‘happiness’.)

To be the ‘best version of yourself’, doesn’t mean seeking perfection. That is unachievable and unachievable goals become self-defeating.

Which brings us back to the beginning of this post: ‘If a thing is worth doing, it’s worth doing well.’ Or maybe even ‘poorly’. But that depends on you defining what ‘well’ is, and perhaps whether you have the capability for achieving that level of ‘well’. Every author, surely, wants to be a ‘good’ writer, but this illusive standard can be soul destroying. If you define ‘good’ by some external standard, and you’re not up to meeting that standard, then you have to make a choice: you either abandon the project, you have to recalibrate your standard of ‘well’, or you keep on working to achieve the high standard (but be careful that this is not the perfection trap).

This whole discussion of quality certainly applies to me as an aging aspiring author. I know I’m a decent writer, occasionally more than decent. I also know I’m not Mark Twain, nor Graham Green, nor Alexander McCall Smith. And probably never will be, for all my striving. I also know (and highly appreciate it) that I have fans of my writing, people who value my work; I also know that I have critical readers, those who judge (not incorrectly) that my writing is amateurish, clumsy, wooden (ouch). I also know that famous and successful authors vary in their readers’ ratings from glowing 5 stars to dismissive 1’s and 2’s. You can’t please all of the people all of the time.

I also know that being ‘a best-selling’ author can be a chimera. ‘Best-selling’ is a surrogate for ‘good’. But many of these books are not very good. Maybe these writers [instinctively or otherwise] understand Crosby’s notion of quality: meet customer requirements, or in publishing speak, know your audience and write for them,

I’m a multi-genre writer, which means each of my books may appeal to different audiences. As I’ve written in many posts before, (marketing, promoting and selling books), knowing your audience and finding your audience are two different things. I have written seven books so far and am working on my eighth. The ‘best-selling’ book is The Treasure of Stella Bay, with more than 300 copies in circulation. The Dynamics of Management is next with perhaps 150 in circulation. One novel has had perhaps half a dozen readers. I still have four or five boxes of The Maxim Chronicles and The Hallelujah Chorus collecting dust in my hall closet. My goal has been, not to get rich, necessarily, but to get read. But how many readers does it take for me to feel I have achieved my goal? Surely more than a couple of hundred. Maybe the books are simply not very ‘good’; or even if they are ‘good’, the marketing effort has not found a sufficient audience for them.

I think of abandoning the field. Give up. I’ll never be a successful writer. I should just accept this hard fact and try to amuse myself with something else.

‘If a thing is worth doing, it’s worth doing well.’

Maybe not. ‘If a thing is worth doing, it’s worth doing poorly.’ Perhaps that’s truer than first thought. I’m not sure about ‘poorly’ – that may be another external subjective trap – but, if it’s worth it to you, it’s worth doing as well as you can. And that is good enough.

Doug Jordan, reporting to you from Kanata, Canada

© Douglas Jordan & AFS Publishing

All rights reserved. No part of these blogs and newsletters may be reproduced without the express permission of the author and/or the publisher, except upon payment of a small royalty, 5¢.