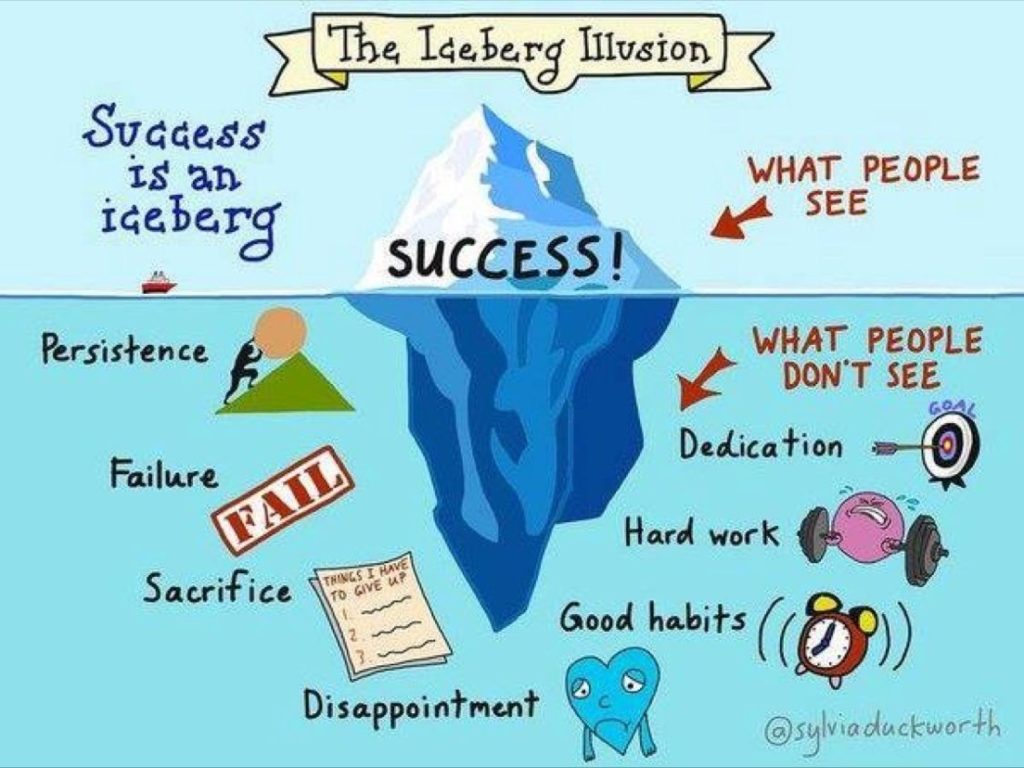

In any worthwhile endeavour, I suggest, success depends on drive, persistence, and endurance. Of course you need talent, a project, some inspiration perhaps, and a little luck, but rare is it that we hit a homerun first time at bat. Even for private projects – hobbies and amusements: accepting a Goodreads reading challenge (read 36 books in 2023), or taking up watercolour painting, golf – in which we are the only judge, success requires completion; and completion takes persistence. It’s easy to start something, it’s another thing to see it through to the end.

All of us have given up on something at some time or other: We’ve lost interest; we’ve run into an intractable problem in our project and don’t want to start over; other problems crop up in our lives; we get diverted by some new interest. We all have a closet full of abandoned projects: the unfinished acrylic painting in the basement, beside the box of old and dry paint tubes and brushes, and easel, caked with old paint; the pile of hemp that used to be some macramé thing, maybe a hanger for a potted plant; those snowshoes taking up space not used for years; a hard-drive full of unfinished manuscripts; a closet full of unsold books.

It’s depressing.

Not to say that we shouldn’t feel perfectly okay with being done with things that no longer hold our interest – stubborn persistence has its own problems – so long as we move on to another endeavour that engages our talents and provides pleasure and satisfaction. But sticking to something that matters to us, even when we are struggling, keeping focused on the goal and finishing, is the measure of success. It’s comparatively easy if it’s a short-term task. But sustaining motivation when the endeavour is longer, multi-year or indeterminant, is much more challenging. When we can see the finish-line we find that last bit of effort to reach it; when the goal is ever-elusive it’s hard to keep going.

Having that feeling of success is hard enough when you are the only judge of your work. Harder when measuring success includes a public dimension, where part of one’s perceived success entails some level of public or external approval.

Writing is one such endeavour.

Lately, for me, achieving that sense of success has been hard.

The challenge of being an author

Sometimes, we in the writing world make a distinction between being a writer and being an author (poets are a whole other thing!). There’s not real agreement on any such distinction but we might say a writer is someone who writes short pieces (articles, ads, press releases) for magazines, blogs or the commercial world, even for just themselves. (I sometimes ask myself if I write these blog posts for myself or do others actually read them. The answer is, yes and some do.) An author writes books, whether traditionally published or self-published; their intent is to produce a substantial piece of work that a reader will invest substantial time in. Many writers write only for themselves, they don’t expect others to read their work, or even would be horrified should anyone see their manuscript; they write only for the challenge of writing, for the personal satisfaction it brings. Like artists in other media – painters for example, who may give away some of their best work to family and friends but don’t expect to become professional artists – most authors don’t expect to find their books on the best sellers list, but they do harbour hope of getting some sort of recognition for their work.

Why would an author even bother to publish if they didn’t want to have people read their books? In fact, we may question if one can even describe themselves as an author if their books never see the light of day. Even if you manage to get your manuscript printed in a conventional book form, with glossy cover and a copyright page, to be recognized as an author – or make the claim – you have to find readers for your book.

And how to get that recognition? You have to take your product to market. And that takes courage, or fool-hardy fantasy.

And how much recognition is enough? How many books do you have to sell to have that feeling of success? You may not expect to get rich and famous from your books (though we do have our fantasies) but you need to sell at least enough books to break even. (I suppose as a wealthy altruist, or crazed narcissist, you could give away large quantities of your books, but that hardly seems legitimate.) A professional-looking book costs about $2000 to produce, mostly in cover design, research, overhead costs such as website and internet fees, print proof costs; if all your sales are through Amazon you make about $1.13 per copy. That means you need to sell 1770 copies just to break even. That’s quite a lot of books. You could almost call yourself a ‘best-selling author’ at that volume.

(I’ve written seven books (and 2 manuals). There are about 700 copies of my books in circulation. Total. Evidently, I’m not a ‘best-selling author’ and I am definitely losing money.)

To sell 2000 copies of your book takes a lot of effort and energy (and more money). To get your book read (or at least delivered) – and more than a few copies to family and friends – you need to have a marketing strategy; you need hustle (and finances) to find distribution channels; and you need to promote your books. And keep it up. That takes determination, persistence, courage; and stamina.

And sometimes those (determination, persistence, courage; and stamina) are in short supply. But knowing that most writers – we champions of hopeless causes – suffer the same dejection, we carry on.

The daunting task of selling books.

Most authors, even the determined ones – and I’m not talking about the closet writers whose manuscripts will never see the light of day – never make serious money writing and selling their books. They need day jobs to sustain themselves (or a good pension). It is one of those Pareto facts that only a small percentage of authors (or almost any artist) will make the lion’s share of the money (and not the 80/20 rule but more like a 99/1 ratio). Consumers (readers) are largely risk averse – they don’t want to risk buying (or even borrowing) a book to read unless it has been recommended in the marketplace: The New York TimesBest Sellers List, a [positive] Globe and Mail book review, the Giller Prize winner, a celebrity author (Michele Obama? Harry Windsor?). A few hundred titles by famous authors will be sold in the millions; a million books by little known aspirants will be sold in the hundreds, or fewer; much fewer.

Publishers are risk averse too, though they assume a lot of the risk every time they agree to take on a new book, and they lose money on most of them. It’s no wonder they will bet on favourites rather than on new entries. J K Rowling allegedly petitioned 112 publishers before one finally took up her first Harry Potter book. Needless to say, she had no trouble selling her second book.

It is estimated that about 3 million books (new titles) are published every year in America, but only about 3000 of those ever make the shelves of Barnes and Noble. That’s 0.1%. nd that’s largely because of the exponential growth of self-published books in the last 10-15 years. For Canadian authors in Canada it’s worse, much worse; this is because Canadian buyers are overwhelmingly influenced by American promotion; most books read by Canadians are by American (or maybe British) authors. And perhaps there’s even a Canadian inferiority complex at play – we don’t really recognize Canadian talent until they ‘make it big’ in America, and then we claim them as our own.

In the face of this daunting market-place for books, most Canadian writers don’t realistically expect to become rich and famous, nor even become ‘best-selling authors’; they just want to be read. (I suppose that might be said of all writers. How many aspiring American authors also live in obscurity, their books languishing in their closets, unsold, unread and unloved.)

But even putting your book out there that takes courage because to be read means the writer has risked ridicule. In reality the public is not particularly harsh in its judgmentalism and criticism, it’s merely disinterested. Knowing this, it’s little wonder a writer will shrink from exposing him or herself in the marketplace. Even a good writer, an accomplished writer, has doubts and has to gird his or her loins each time she takes another tilt at that windmill of elusive fame.

So the aspiring author faces two risks – of ridicule and of penury. Even if he is content to merely cover his costs in publishing his book, is 1770 copies sold enough to satisfy that need to ‘be read’?

My best book – The Treasure of Stella Bay – has sold about 250 copies. I like this book and many of my readers who have given me feedback like it too. My book is in 15 retail outlets. By the summer of 2022 I was beginning to feel a measure of success. But sales have slowed; 250 copies is not 1770 copies, and my retailers are beginning to think it’s time to pull my book from their shelves.

So I ask myself, is it time to give up on this author project? I’m beginning to run out of stamina, and will?

Let’s continue this discussion in the next post.

Doug Jordan, reporting to you from Kanata, Canada

© Douglas Jordan & AFS Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of these blogs and newsletters may be reproduced without the express permission of the author and/or the publisher, except upon payment of a small royalty, 5¢.