In my previous blog post, Turning Into My Dad, I described, with as light a hand as I could, some of the ailments that tend to befall men as they enter their golden years. I’m sure women have some of their own issues when it comes to ageing and observing their own physical decline; for the most part they even get a head start on men – menopause in their early fifties. Ultimately both sexes are forced to recognize they are not the same person they once were, and there’s no going back. We become increasingly aware of our mortality.

Ha! The ‘golden years’! There’s nothing golden about the golden years, except perhaps increasing lack of bladder control. I remember – too well, and not particularly fondly – visiting my Mom over her seven years’ residency in the Peterborough Manor. This was a very attractive and well run ‘retirement home’ in the North End of Peterborough providing assisted living to the residents lucky enough to have found a home there. But the certain evidence of the golden years of the residence was the persistent stench of urine throughout the complex. Probably most, if not all, of the residents wore adult diapers. It’s hard to know if they were aware of this condition and embarrassed by this assault on their dignity. I’m not sure if this was yet another of Mom’s old-age afflictions – she suffered early symptoms of dementia, had a congestive heart condition and suffered constant pain from osteo-arthritis – but she was always very fastidious about her appearance and her toilet and never mentioned this as a problem for her; but then, being a rather private person, why would she?

Mom was quite happy at Peterborough Manor for her first five or six years, but even assisted living couldn’t hold back the continuous decline in cognitive and physical ability she faced. In fact, her dementia may have been her saving grace: she didn’t choose to move to Peterborough Manor, but after the fact, she thought she had. To what extent was she cognitively aware that the next step from the ‘rest home’ was permanent rest in Little Lake Cemetery? Loss of cognitive function was long a concern for her and she pursued the usual strategies for staving off mental decline – reading, socializing as much possible (for an introvert), mostly in her church. She even learned to enjoy playing cards and doing crossword puzzles, two activities she dismissed in her own mother.

The ‘Travels With Myself’ blog is a series of mental musings about the issues in my life. Many of them have been floating around in my skull for ages but took on more active refection in the last ten years or so, particularly during, and since, the time of Marlene’s, and inevitably my, journey with her illness and ultimately death from cancer. I don’t publish these bogs merely for self-indulgence, or even for self-therapy, (self-parody maybe) but because in some fashion or other I sense that the issues I explore are issues that most of my readers also think about, or become aware of, in some form or other, in their own lives. My hope is that these posts provoke more conscious thinking in the reader. My motto, as you may recall, is, to entertain, possibly to educate; or maybe it’s the other way around. In fact most people are willing to be entertained (hence all my blogs contain some snippets of humour, even if ironic or dark) but most readers resist being educated, especially if it feels like a lecture.

For much of my life I’ve considered the problem of mortality, its existential and spiritual dimensions, and the various solutions contrived by human beings. Human beings, because of their [possibly] overdeveloped brains, may be the only animal on Earth concerned with this problem. All the others are blithely unaware, perhaps luckily for them.

Gradually over my lifetime I have become a fairly entrenched agnostic. I seriously doubt the existence of a god; or, at the very least, not without a radically redefined notion of god. I don’t think there is such a thing as a soul separate from our bodies and brains (I even question consciousness for that matter – our brains are merely predictive machines which have created an illusion of a self-image) and so I don’t think there is any such thing as an afterlife, a haven for disembodied souls.

Despite this, I’ve always had a certain fascination with cemeteries. Even as an eleven-year-old living in Sudbury I was attracted to the cemetery that was just a few houses down the hill from our house on Buchanan Street. What eleven-year-old has not wondered about cemeteries, a vaguely compelling dread of spectres ‘living’ there. But the fascination in Park Lawn Cemetery in wasteland Sudbury was the grass and the trees – this was almost the only greenspace in all of sulpherous Sudbury in 1958. As an adult the park-like quietude of cemeteries attracted me, especially old cemeteries with greying headstones and towering trees. But I also was aware that cemeteries were more than peaceful parks, they also held the bones and lost stories of all its dwellers there. I would often study the inscription on a gravestone and wonder what that person’s life had really been about: her triumphs and fears, her joys and sorrows, his loves and losses. What did she die of? What did she think about at her moment of death?

I found exploring cemeteries profoundly thought-provoking. Marlene found it mildly morbid. I understand her point of view, even though I doubt she understood mine.

To my regret, we rarely talked about what she thought about at the prospect of her own demise. I think, for most of her illness, she lived in cognitive dissonance: she knew she was terminal, but she remained hopeful, almost to the end, that she might live, that she might yet magically be cured. I don’t think she wanted to be immortal, but I’m pretty sure she was disappointed that she wouldn’t be around to see how things turned out, especially for the grandchildren.

And who could blame her? Dealing with death is difficult enough, but when it’s your own death, it’s another story altogether. In the end, I don’t know what she thought would happen ‘after’. Did she still hope there would be a heaven, a peaceful place where she would be safe, and she could continue to watch the lives of her progeny unfold?

Dr. Andrew Weil in his book, ‘Healthy Aging’ [2005], suggests that medical science may not be far from solving the question of immortality, at least at the cellular level, but he warns that the risks to the host may nevertheless be fatal in the form of malignancy.

And even should we live a perpetual life, would it be worth it? The ancient philosophers and mythographers thought not. For two classic stories on the price of immortality, you should investigate the Tithonus disaster, in which Zeus grants Tithonus immortality but not perpetual youth; and, the fate of the Wandering Jew, Christ’s curse of the man who refused him rest, to wander the earth for all eternity and find no rest.

I’m inclined to agree with Weil in this regard. Immortality may not be the desirable result we think we want. It might be exciting to see how the world turns out in terms of scientific discovery, and all manner of change to our planet and human society; and I wouldn’t mind seeing my grandchildren graduate and marry and have happy lives of their own. But there has to be a limit. Surely we would get tired of family; and if all our friends have similar longevity, will we still find them satisfactory friends?

Failing bodily immortality, many religions offer another solution – eternal life after death; but is this merely of the immortal soul? I suspect many people harbour the fantasy that life after death also includes the resurrection of the body. (But then, which body would it be, your 17-year-old perfect specimen, or your 78-year-old wizened one?)

So instead of immortality we must face, eventually, the inevitable – mortality.

Dr. Weil doesn’t actually address this question; his whole proposition is living the ageing stage of life gracefully, largely ignoring the question of dealing with death gracefully. His ageing formula is not surprising – living healthily through [anti-inflammatory] diet and exercise, accepting our limitations and eschewing the societal meme of youth, and finally, living a life with purpose. This indeed is the formula for every stage of life.

Transitioning to the last stages of life is yet another example of the difficulty we have in dealing with change, and everyone has misgivings about change, regardless of what they say. Change may be the tension between opportunities (positive) and loss (negative). (Force field analysis, Kurt Lewin). To successfully adapt to change, says Lewin, the forces for change need to exceed the forces for resisting the change. The trouble is, it’s a lot easier to see the things we lose in ageing than the opportunities ageing presents. Accepting ageing is a cognitive process but it is also an emotional process. The serious challenges ageing afflicts on our psychological identity should not be trivialized. I personally have wrestled with this question for a number of years, and have had significant difficulty with acceptance of this change. I’m even investigating psychologists who might offer transition counseling, or merely conversation. Ageing gracefully is not coming easily for me.

But even as I learn to accept ageing as an unavoidable stage of life, how does this help deal with the questions of death? I think death is not only the inevitable outcome – there can be no denial – it is also the correct outcome of life, as it is for every species; but to personally transition to this state with equanimity is surely hard.

I think Samuel Johnson’s famous quote probably untrue for many: ‘The prospect of one’s imminent demise concentrates the mind wonderfully’. He had been speaking of the gallows which is a fairly specific event but for most of us the prospect is hypothetical. What Johnson had in mind, I think, was the prosect of one’s certain death spurs one to action – get your affairs in order, sort out the detritus of a life and make it as easy as possible for your surviving family. Without that imperative, most of us just procrastinate and delay, or push off thinking about it altogether.

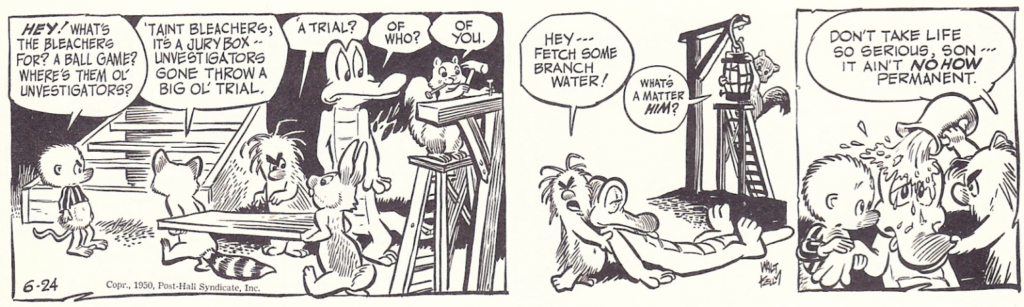

Here’s the great philosopher, Pogo, (Walt Kelly) on a similar theme:

Most people think of death fearfully: hence the source, likely, of Woody Allen’s famous denial: ‘I’m not afraid of death. I just don’t want to be there when it happens!’

Often this fear is of the presumed physical pain in the process of dying – which is why most of us hope for a swift death. But more than pain there is the great uncertainty: what actually happens to me after I have died? To quote Pogo, again[1]: ‘The fear of uncertainly is worse than the certainty of fear’. Which is another reason why people wish for not only a swift death but a sudden death, an unexpected, completely unaware death: a fatal stroke, preferably while we are asleep; a crack on the skull. In sudden death we are spared the suffering that accompanies the fear of uncertainly.

In many ways, death is the ultimate change. But the problem for most people is that the opportunities are uncertain, the losses well-understood. After one’s death, the ‘opportunities’ are likely oblivion, but the losses are the entirety of our identify and everyday experience.

It’s unlikely you think as I do (we should hope not!) but these days I often think ‘last things’: Is this the last time I will drive down Wellington Street and study the majestic Parliament Buildings? Will I ever see Paris again? How many times in 70 years have I made the [usually] peaceful drive down Hwy 7 to Peterborough? How many more will there be? And so many other life experiences that will not likely recur for me. I even take it a step further and reflect on the fact that all these physical and geographic phenomena will still be here after I’m gone, but I won’t be here to experience them. These are sobering thoughts, melancholic even. But this is life. And this is death.

So, the problems of aging are difficult enough, the questions of mortality more so.

In our next post I wish to discuss a variant on this question: suicide.

Doug Jordan, reporting to you from Kanata, Canada

© Douglas Jordan & AFS Publishing

All rights reserved. No part of these blogs and newsletters may be reproduced without the express permission of the author and/or the publisher, except upon payment of a small royalty, 5¢.

[1] Or was it Virginia Satir: ‘People prefer the certainty of misery to the misery of uncertainty.’